![]()

I. WHAT IS THE COST-OF-LIVING REFUND?

I. WHAT IS THE COST-OF-LIVING REFUND?

The Cost-of-Living Refund is an expanded and modernized version of Michigan’s current state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which will allow more Michigan families to qualify for a larger credit. Michigan’s EITC has already been effective in improving tax fairness and providing more economic security for working families. Strengthening our state EITC to reach more working families, allowing them to claim larger state credits, and modernizing the credit to include students and caregivers will help us create a Michigan that works for everyone.

The federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), enacted in 1975, is an income tax credit that helps offset the regressive effects of taxes on families with low incomes. It rewards work, helps people keep working by allowing them to afford car repairs or child care, is a proven-effective antipoverty tool, and has long-lasting positive impacts on children in families that receive it. It has been so successful that it was expanded under both Democratic and Republican presidential administrations.

The specific credit amount depends on the worker’s income, marital status and number of children. Workers begin to earn it with the first dollar of income, and the credit rises as income rises until gradually phasing out at higher incomes. An important feature of the EITC is that it is refundable, meaning that if the credit exceeds the worker’s tax liability, they can still receive the credit in a cash refund.

Nationally in 2016, a family with children received an average federal EITC of $3,176, boosting monthly incomes by $265. In contrast, a taxpayer without children received an average federal credit of $295 that same tax year.1 In 2018, Michigan families claimed an average federal EITC worth about $2,523 for the 2017 tax year and prior years.2 Families can use the additional income to pay for basic necessities, home or car repairs, or pay down debt.

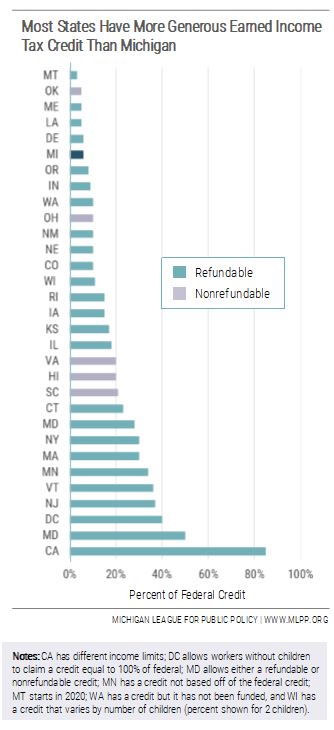

Michigan is among the 29 states and Washington, D.C. that have decided to augment the impact of the federal EITC by implementing their own income tax credits. Michigan’s EITC was enacted in 2006 and became effective in 2008. Beginning in tax year 2012, our state EITC was reduced from 20% of the federal credit to just 6%. Most states that offer an EITC have a more generous credit than Michigan. For example, Michigan has the lowest credit of Great Lakes states.

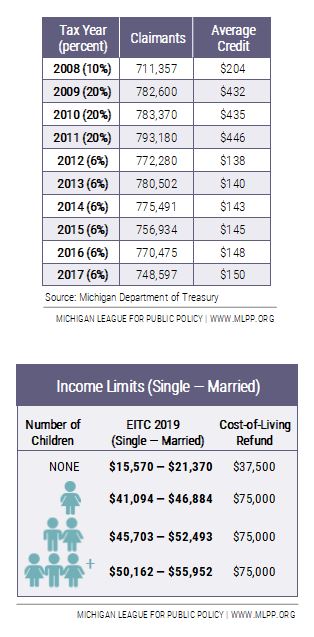

In 2017, more than 748,500 Michigan taxpayers claimed the state EITC with an average credit of $150; however, in 2011, when the credit was last equal to 20%, almost 793,200 taxpayers claimed an average credit of $446. In 2011, it helped pull more than 22,000 families above poverty. By 2014, its benefit had dropped but still helped pull about 6,500 families above poverty.

In 2017, more than 748,500 Michigan taxpayers claimed the state EITC with an average credit of $150; however, in 2011, when the credit was last equal to 20%, almost 793,200 taxpayers claimed an average credit of $446. In 2011, it helped pull more than 22,000 families above poverty. By 2014, its benefit had dropped but still helped pull about 6,500 families above poverty.

Like the EITC, the Cost-of-Living Refund is designed to encourage work while also boosting the incomes of Michiganders with low to moderate incomes and improving tax fairness in the state. It would expand and modernize our current state EITC. Here’s how:

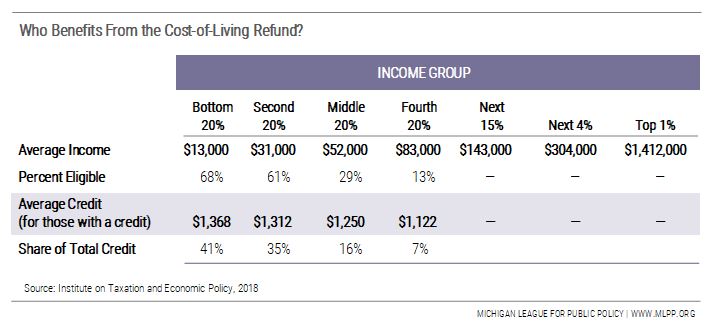

- The Cost-of-Living Refund would provide a basic $1,200 credit or up to 50% of the federal EITC, whichever is higher, (a significant increase from our current 6%) for Michigan families earning less than $75,000 ($37,500 if not raising children).

- The amount of the credit would depend on the number of children in the household and income level. If the credit were in place for 2019, families with three children would receive a credit up to $3,279 while a one-child family would see up to $1,763.

- The Cost-of-Living Refund also expands eligibility by including young workers not raising children in their own homes under the age of 25, students who are pursuing higher education at least half-time, and caregivers caring for a child under 6, a family member with a disability, or a relative over the age of 70.

- The credit would be available in monthly installments, allowing families to better make ends meet by covering monthly bills.

- Like the EITC, the Cost-of-Living Refund is fully refundable. It would be paid for by eliminating Michigan’s unfair flat income tax and replacing it with higher tax rates on incomes over $250,000.

Cost-of-Living Refund Would Provide a Cost-of-Living Boost to Nearly 3.6 Million Michiganders

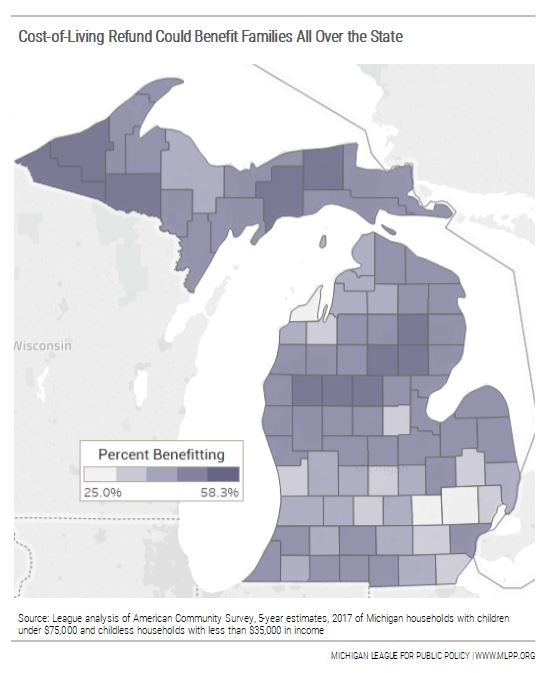

The Cost-of-Living Refund would provide an income boost to nearly 3.6 million Michiganders, including 1.4 million children. About 34% of Michigan families would benefit, including about 43% of taxpayers making under $105,000 a year. Over 50% of Michigan children would benefit from the Cost-of-Living Refund. At its current rate and income limits, only about 16% of Michigan families receive the EITC, and only 37% of Michigan children benefit.

The amount of the credit would, like the EITC, still depend on the taxpayer’s income level and the number of children in the family. Michiganders with three kids making between $14,500 and $18,000 would receive the largest credit—about $3,279. A family in the same income bracket with two children would receive a credit of about $2,914.

The Cost-of-Living Refund also recognizes the importance of caregiving and pursuing further education. Under current law, a family must have earned income—either through an employer or self-employment—in order to qualify. This ultimately means that many students and people caring for young children, elderly family members or family members with a disability cannot qualify for the EITC. The Cost-of-Living Refund would provide these individuals with a basic credit of $1,200 even if they have no income, acknowledging that they do work and contribute to Michigan’s economy.

Young workers end up in the same situation with the EITC. Under current federal requirements, young workers—those under age 25—do not qualify for the EITC unless they have children. This leaves many young workers not raising children in their own homes—including noncustodial parents and recent college graduates just starting their careers—being taxed into or further into poverty through our state and federal tax codes. The Cost-of-Living Refund rectifies this by allowing single workers without children to qualify for a credit worth up to $1,200.

Young workers end up in the same situation with the EITC. Under current federal requirements, young workers—those under age 25—do not qualify for the EITC unless they have children. This leaves many young workers not raising children in their own homes—including noncustodial parents and recent college graduates just starting their careers—being taxed into or further into poverty through our state and federal tax codes. The Cost-of-Living Refund rectifies this by allowing single workers without children to qualify for a credit worth up to $1,200.

Giving a Hand Up to Michigan Taxpayers With Low and Moderate Incomes

Michigan’s economic recovery is often discussed, but the recovery hasn’t affected all Michiganders equally and many still feel left behind. While only 1 in 6 Michigan residents live below the poverty line, even more (1 in 3) live with low incomes and still struggle to make ends meet—pay for housing, food, child care, transportation and healthcare—let alone get ahead or save for college or retirement.

Unfortunately, at the same time, Michigan lawmakers have continued to implement policies under the guise of “getting people back to work,” when they really just kick needy families off of much-needed programs. For example, lawmakers have implemented a strict 48-month lifetime limit on cash assistance, resulting in many Michiganders being denied assistance even though extreme poverty remains high. Additionally, while many states were eliminating their asset tests on food assistance, Michigan implemented its own, making many families who are going through a temporary struggle—such as a job loss or the death of one of the family’s main workers—ineligible for help with buying food.

Unlike these policy changes, the Cost-of-Living Refund would provide many Michiganders a hand up. It would help Michigan families address challenges and pay for basic needs, pay down debt, and perhaps get ahead. Michigan should pursue the Cost-of-Living Refund to help right-size our upside-down tax code, give a hand up to Michigan workers who have been left behind by the recovery and state policy changes, and to have a lasting benefit on Michigan’s residents and communities statewide.

II. MAKING MICHIGAN’S TAX CODE FAIRER

Michigan succeeds when all of its residents are successful. Despite the state’s recent recovery, many Michiganders continue to struggle with their basic needs while the richest residents see rising incomes. This is in part because Michigan’s overall state tax code makes it harder for its residents with low to middle incomes to succeed.

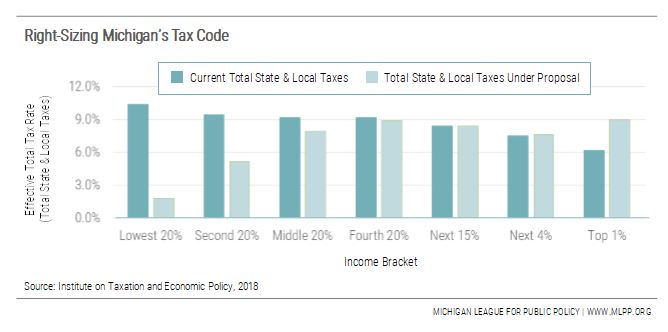

Michgan’s tax code is upside-down, meaning taxpayers with low incomes pay a higher portion of their incomes in state and local taxes than wealthier Michiganders. While Michigan’s income tax is slightly progressive despite its flat rate due to refundable credits—like the Homestead Property Tax Credit, also called the circuit breaker, and Earned Income Tax Credit—Michigan’s sales, gas and property taxes are highly regressive. Michigan’s poorest taxpayers ultimately pay an overall state and local tax rate over one and a half times the rate of Michigan’s richest residents.

Michiganders With Low Incomes Pay More of Their Income in Taxes

Of the 41 states with a broad-based income tax, Michigan is one of nine states with a flat income tax—currently set at 4.25%. Michigan’s flat tax requirement is set in the state constitution so any change toward a graduated income tax—like the federal income tax—would require a vote of the people. Flat income taxes are generally regressive, meaning even though the same rate is levied on all levels of income, lower income taxpayers pay a higher percentage of their income in taxes. However, because of income tax credits like the circuit breaker, and the state EITC, Michigan’s income tax is somewhat progressive. The most vulnerable Michiganders, making less than $17,600 a year ($10,000 a year average), pay 0.7% of their income in income taxes. The middle class—making between $33,000 and $57,100 a year (average $43,000)—pay an effective income tax rate of 2.7%. The richest Michigan residents, making more than $422,100 a year ($1,245,000 on average), pay 3.8% of their incomes in income taxes.

However, Michigan’s highly regressive sales and property taxes more than offset the slight progressivity of its income taxes. Combined, the poorest 20% of Michigan residents pay 9.6% of their incomes in property, sales and other excise taxes—about 4 times the effective property, sales and excise tax rate of the richest Michiganders. This is because taxpayers with low to moderate incomes spend more of their monthly incomes on basic needs, such as housing, transportation and toiletries, than taxpayers with higher incomes, and these items are subject to regressive property and sales taxes. Ultimately, this means that Michigan’s taxpayers with the lowest incomes pay the highest share of their incomes in state and local taxes, and the highest income earners pay the lowest share.

2011 Tax Shift Left Taxpayers With Low to Moderate Incomes Behind

Part of Governor Rick Snyder’s first budget included a significant tax shift from businesses to individuals. To help pay for a tax cut for businesses, the administration and Michigan Legislature cut or eliminated tax benefits for residents, including reducing the state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) from 20% of the federal credit to 6%. In 2011, more than 793,000 Michigan taxpayers received an average credit of $446. The next year, this benefit had dropped to an average of $138.

In tax year 2017, more than 748,500 taxpayers received an average credit of $150. However, had the credit been worth the 20% it used to be, the average credit would have been worth $500. The additional $350 could have gone far in helping families make a home or vehicle repair, catch up on bills, pay down debt or simply make ends meet. This would have allowed nearly $262 million more to flow into local economies than at the current rate.

In tax year 2017, more than 748,500 taxpayers received an average credit of $150. However, had the credit been worth the 20% it used to be, the average credit would have been worth $500. The additional $350 could have gone far in helping families make a home or vehicle repair, catch up on bills, pay down debt or simply make ends meet. This would have allowed nearly $262 million more to flow into local economies than at the current rate.

In recent years, many of the changes made as part of that initial tax shift have been reconsidered. Each legislative session, lawmakers have introduced and voted on bills that would restore credits for charitable giving. In addition to introducing bills to restore the generous exemptions for certain retirement income, lawmakers have made tweaks to these exemptions to lessen the impact of the tax. What’s more, a triggered income tax rate cut that disproportionately benefits wealthy taxpayers was enacted, which will eventually eliminate our income tax and rid the state of our most progressive tax in our tax code. Even though bills to restore our EITC to previous levels, or boost it even beyond, have been introduced each legislative session, there has been no movement on the bills, leaving taxpayers with low to modest incomes still behind.

The Cost-of-Living Refund Will Help Make Michigan’s Tax Code Fairer

Because Michigan’s tax code relies predominantly on regressive sales and property taxes and constitutionally-mandated flat income tax, refundable income tax credits remain the best way to make our tax code fairer. The Cost-of-Living Refund would enhance our current EITC by increasing the credit and expanding the income eligibility to $75,000 ($37,500 if the taxpayer has no children). The credit would be paid with by changing our constitution to allow a graduated income tax and by raising taxes on the top 5% of Michigan taxpayers. The proposal would create a graduated income tax with four brackets: $0+ at the current 4.25% rate; $250,000+ at 6%; $500,000+ at 8%; and $1,000,000+ at 10.25%.

It’s important to note that these new rates would not be levied on income as a whole. Instead, the higher rates would only be levied on the income above the lower limit. So a taxpayer who has taxable income of $300,000 would pay the current 4.25% on the first $250,000 in income and would pay the 6% rate on the income above $250,000. Only about 2% of Michigan taxpayers would see a tax increase under this plan.

Implementing a graduated income tax and enacting the Cost-of-Living Refund would help rebalance our tax code. Taxes should be based on the ability to pay, with higher-income earners able to pay more in state and local taxes than earners with lower incomes.

Under the plan, taxpayers in the bottom 80% would see their effective tax rate decrease. Instead of our poorest taxpayers, those making less than $17,600 a year, paying 10.4% of their income in state and local taxes, they would pay 1.8%. Michigan’s middle class would go from paying 9.2% of their income in state and local taxes to 7.9%. Only taxpayers among the top 1%, making on average of $1.2 million, would see a significant tax increase going from spending 6.2% of their income in state and local taxes to 9%. And we shouldn’t shy away from raising taxes on the top 5% of taxpayers, as these Michiganders are the ones who benefitted most from the federal tax cuts enacted in 2017.

It’s interesting to note that under this proposal, many taxpayers in the top 20% will see no or little change in their overall tax burden, and will still pay lower effective tax rates than middle class and upper-middle class taxpayers.

Disputing the Millionaire Migration Myth

Taxing millionaires and other high-income earners at higher rates will not cause them to move their families to a different state, nor will it cause economic decline. Over the past two decades, a number of states and the District of Columbia have enacted rate increases targeted to high-income earners (a “millionaire’s tax”) as a way to raise much-needed revenue. A recent analysis of seven states (California, Connecticut, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York and Oregon) and the District of Columbia that have millionaire’s taxes showed that seven of these states had per capita income growth at least as strong as their neighbors, six had economic growth at least as good as their neighbors, and five states had job growth at least as strong as their neighbors.3

Additionally, a 2016 analysis of the roughly 500,000 families with income of $1 million or more showed that only 2.4% of these families moved states in any given year, compared to 2.9% among the general population.4 In fact, state migration was actually highest for taxpayers with low incomes at a rate of 4.5% for taxpayers earning around $10,000.5 While taxes may be a factor that companies and families use to decide whether to move to a state, it is not the sole factor nor likely one of the most important factors.

III. NOW IS THE TIME TO PROVIDE WORKERS A HAND UP

In 2010, Michigan, like the rest of the nation, began to emerge from the Great Recession, a recession that hit our state longer and harder than any other state. Michigan’s decade-long recession in the first part of the 20th century resulted in more than 850,000 lost jobs, near record-high levels of unemployment and rising poverty. Although the state is nearing a decade of expansion, many Michigan residents feel the recovery has left them behind. Now is the time to establish a Cost-of-Living Refund to not only help Michigan’s taxpayers with the lowest incomes, but also those working families, including students and caretakers, that have been left behind with the growing divide between Michigan’s upper-income residents and the rest of us.

Too Many Michigan Families Struggle to Make Ends Meet

While Michigan’s poverty rate has finally dropped below levels we saw in 2008, too many Michigan residents still struggle regularly, and nearly one-third of Michigan residents live with wages that put them either in poverty or with low incomes (below 200% of poverty). Many of the residents who fall above poverty but still are unable to make ends meet are ineligible for benefits, such as cash or food assistance or healthcare through Medicaid.

The Cost-of-Living Refund can build on the effectiveness of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) as an anti-poverty tool. In tax year 2015, the state EITC helped pull about 6,550 families above the federal poverty level, but when the state EITC was last 20% in 2011, it helped pull about 22,000 Michigan families above the federal poverty level. With the Cost-of-Living Refund being equal to 50% of the federal credit, the credit’s anti-poverty capabilities will be multiplied.

The Cost-of-Living Refund can build on the effectiveness of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) as an anti-poverty tool. In tax year 2015, the state EITC helped pull about 6,550 families above the federal poverty level, but when the state EITC was last 20% in 2011, it helped pull about 22,000 Michigan families above the federal poverty level. With the Cost-of-Living Refund being equal to 50% of the federal credit, the credit’s anti-poverty capabilities will be multiplied.

Over the past decade, both Michigan and the nation as a whole have seen incomes grow, but Michigan’s income growth has lagged behind both the nation and many neighboring states. In 2008, Michigan’s median household income ($48,591) was less than $3,500 below the nation’s median household income ($52,029). By 2017, this gap had grown to nearly $5,500, with Michigan’s median household income sitting at $54,909 compared to the national median household income of $60,336. This means that over the past decade, Michigan’s median household income grew 13% while the national median household income grew 16%. Over the same period, only Illinois and Indiana saw slower growth than Michigan of neighboring states. Both Wisconsin and Minnesota saw more robust household income growth than Michigan, with Minnesota’s median household income growing by about 19.4%. What’s more is that Illinois, Minnesota and Wisconsin also had higher median household incomes than Michigan in 2017.

However, incomes are becoming more concentrated in high-earning households. In 2017, according to the most recent census data, the top 20% held 50% of the total amount of Michigan’s income while the bottom 20% held less than 3.5%. What’s more, the top 5% held nearly 22% of the state’s total income. A recent analysis tells a similar story. In 2015, Michigan ranked as the 15th most unequal state in terms of income inequality, and this income inequality has been growing since the 1970s. The top 1% took home 17.8% of all the income in Michigan and made 21.4 times more than the bottom 99%.6

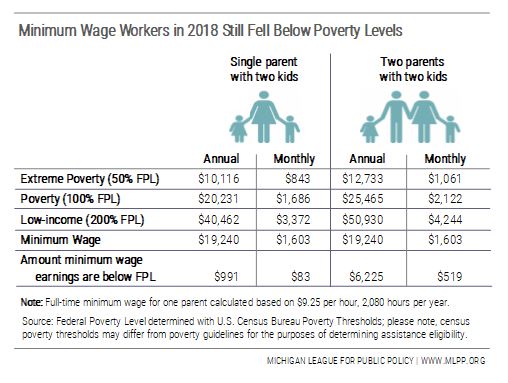

The Cost-of-Living Refund can help build on the minimum wage increases that have been enacted in Michigan. In 2014, former Governor Snyder signed into law changes that gradually increased the minimum wage from $7.40 to $9.25 an hour starting in 2018. In 2018, through a citizen-initiated petition and legislative action, Michigan’s minimum wage will reach $12.05 by 2030—roughly 20 to 30 cents per hour increases per year.7 Robust state EITCs—which are similar to the Cost-of-Living Refund being proposed here—work in concert with minimum wage increases to really boost incomes, improve self-sufficiency, and lessen the gap between high-income earners and families with low incomes.8 Enacting the Cost-of-Living Refund as our minimum wage increases would have a significant impact on Michigan families with low and moderate incomes.

Jobs Trends Show Need for the Cost-of-Living Refund

Michigan’s unemployment rate has declined significantly since its near 15% high during the recession, but this does not show the full picture of Michigan’s economy and job market. For many in Michigan, high-wage jobs remain out of reach due to systemic barriers that make workers unable to access postsecondary education or certifications, such as having unreliable child care or lacking transportation. This leaves many workers stuck in low- to moderate-wage jobs with no ability to climb the ladder or having to cobble together multiple jobs to make ends meet.

In the most recent United Way ALICE (Asset Limited, Income Constrained Employed) Report, low-wage jobs continued to dominate job trends, with 61% of all Michigan jobs paying less than $20 per hour, and almost two-thirds of these jobs paying less than $15 per hour.9 Using the ALICE standard, a single person in 2017 needed to work full time making $10.52 per hour. A married couple with two children, one infant and one preschooler, needs to have combined wages of $61,272 a year, or an average hourly wage of $30.64. Many of the most common jobs would not allow a family to make ends meet, and a single adult would need to work many of these jobs full time or nearly full time.10 In 2017, the average hourly wage of all employed persons was $23.22. However, of the 10 occupations with the most people employed, nine paid less than the average hourly wage.

In the most recent United Way ALICE (Asset Limited, Income Constrained Employed) Report, low-wage jobs continued to dominate job trends, with 61% of all Michigan jobs paying less than $20 per hour, and almost two-thirds of these jobs paying less than $15 per hour.9 Using the ALICE standard, a single person in 2017 needed to work full time making $10.52 per hour. A married couple with two children, one infant and one preschooler, needs to have combined wages of $61,272 a year, or an average hourly wage of $30.64. Many of the most common jobs would not allow a family to make ends meet, and a single adult would need to work many of these jobs full time or nearly full time.10 In 2017, the average hourly wage of all employed persons was $23.22. However, of the 10 occupations with the most people employed, nine paid less than the average hourly wage.

In the next several years, lower-wage jobs will continue to dominate the workforce. The most job openings are anticipated to be in food service, including fast food, which continues to have wages at or near the minimum wage. Where Michigan projects the most growth, some jobs, including home health aides (44%) and personal care aides (36.6%), still have wages that top out at $12 per hour.11

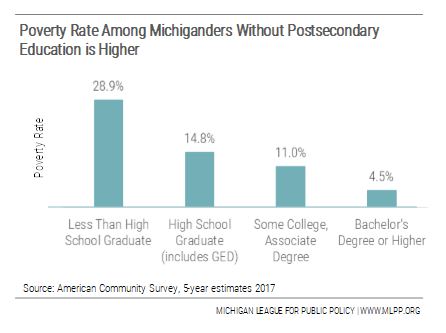

Practically all of the high-demand, high-wage jobs projected to open in the next several years require a postsecondary certificate or degree or licensure, and those that don’t require some on-the-job training.12 However, for many Michigan residents, the costs of obtaining a postsecondary education, certification or degree are a barrier or students have to take on increasing amounts of debt in order to pursue college.13 In fact, less than 40% of Michigan’s population has an associate degree (9.3%), bachelor’s degree (17.1%), or graduate or professional degree (11%). Higher-wage in-demand jobs are inaccessible to roughly 60% of Michigan adults due to lack of higher education or training, and many will remain stuck in low-wage jobs, making it difficult for them to make ends meet.

Practically all of the high-demand, high-wage jobs projected to open in the next several years require a postsecondary certificate or degree or licensure, and those that don’t require some on-the-job training.12 However, for many Michigan residents, the costs of obtaining a postsecondary education, certification or degree are a barrier or students have to take on increasing amounts of debt in order to pursue college.13 In fact, less than 40% of Michigan’s population has an associate degree (9.3%), bachelor’s degree (17.1%), or graduate or professional degree (11%). Higher-wage in-demand jobs are inaccessible to roughly 60% of Michigan adults due to lack of higher education or training, and many will remain stuck in low-wage jobs, making it difficult for them to make ends meet.

The Cost-of-Living Refund recognizes the important—but unpaid—work that students do by allowing them to receive a $1,200 basic credit if they have low or no incomes. Many students are not currently eligible for federal or state EITCs because they are either young and childless or because they have no other earned income. In light of the need for higher-skilled workers, the state should be breaking down barriers to accessing postsecondary education. The Cost-of-Living Refund helps give a boost to these students, offsetting the high cost of attaining a post-secondary education, and may allow them to go farther and earn higher wages as an adult.

IV. COST-OF-LIVING REFUND WOULD BENEFIT ALL MICHIGAN COMMUNITIES

The Cost-of-Living Refund, like our current state EITC, would benefit Michiganders of all races and ethnicities statewide, including urban and rural areas. Additionally, the Cost-of-Living Refund would boost economic activity in the areas where it is received and have long-lasting positive impacts on children who receive it.

Cost-of-Living Refund Has Statewide Benefits

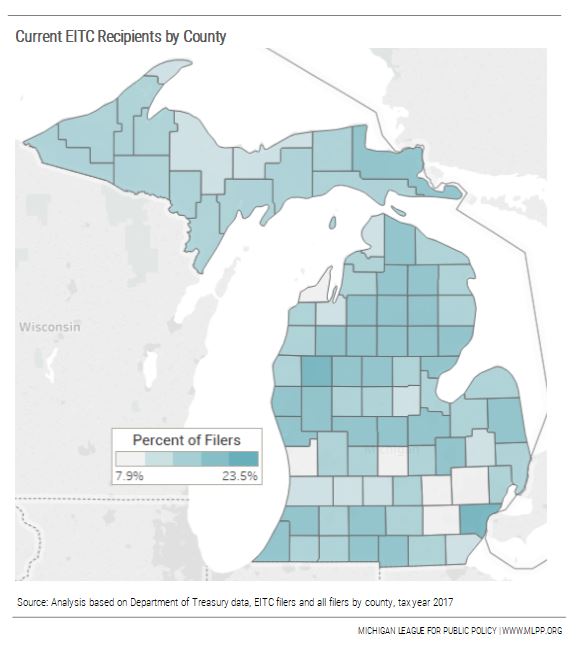

One of the biggest complaints about the Earned Income Tax Credit is that it does not help enough families and there is a misconception that it does not have a stronger impact outside of our urban cores. Income limits set by the federal government dictate who qualifies for our state EITC, and these limits mean only about 16% of our families currently qualify for the credit. And while urban communities tend to see the bulk of the EITC returns in terms of sheer numbers (largest number of filers with the EITC in Wayne, Macomb, Oakland, Kent and Genesee counties), our current EITC actually has a statewide impact when looking at the EITC recipients as a percent of the total tax returns filed in each county. In fact, more than 1 in 5 taxpayers in Lake County received an EITC in tax year 2016, and about 20% of filers in Wexford, Clare and Muskegon counties received the EITC (Wayne County still had the highest percentage of EITC recipients).

The EITC could do so much more, though. By expanding income limits to $75,000 ($37,500 if the household has no children), more than 1 in 3 Michigan families (34%) would qualify for the Cost-of-Living Refund. Lake, Oscoda, Clare, Gogebic and Iron counties come out on top when looking at the percentage of families that could qualify for a credit based on the number of households falling below $75,000 in income ($37,500 if no children are present regardless of marital status). In terms of numbers of families that would benefit, the counties of Wayne, Oakland, Macomb, Kent and Genesee would still have the greatest number of families eligible for the Cost-of-Living Refund, but this is likely a result of the fact that they have the largest populations.

Childless Adults—and Some Workers Without Incomes—May Qualify

Quirks in the federal tax code make many adults—including caregivers, noncustodial parents and workers just starting their careers—ineligible for the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). To begin with, an EITC recipient must have earned income from a job or self-employment; caring for a child or an elderly or disabled relative does not qualify as work, nor does attending higher education at least half time. Students, parents and adults caring for ailing parents or relatives are working, and the Cost-of-Living Refund recognizes these individuals’ contributions by allowing them to qualify for a basic credit of $1,200 or up to 50% of the federal EITC, if they would have been eligible.

Additionally, childless adults remain as the sole group that state and federal tax codes tax into or deeper into poverty, and poverty rates among young adults in Michigan remain high, especially for young adults of color. Single adults without children must be at least 25 or under 65 in order to qualify for a federal EITC. This leaves many childless adults, including some parents who do not have custody of a child for tax purposes but are still helping raise the child, out of eligibility for the credit. If a childless adult does qualify, he or she only receives a very small amount federally, which significantly reduces their state credit. In tax year 2018, childless adults are only eligible for a credit of up to $519, which, at 6%, only affords them a $31 state tax credit. The Cost-of-Living Refund remedies this by affording workers not raising children in their own homes making less than $37,500 a credit worth up to $1,200.

An Important Tool in Racial Equity

An Important Tool in Racial Equity

Due to systemic structural barriers, workers of color are often more likely to earn poverty-level wages than White workers. State-level EITCs help offset the disparate racial impact of regressive taxes like the sales tax by boosting the after-tax income of households with low incomes. Additionally, while state EITCs serve a larger number of White households, due in part to population size, they serve a larger proportion of people of color. A recent analysis of EITC-eligible households nationally show that about half of all EITC-eligible taxpayers are White. The same report found that nearly 40% of eligible households are Black or Latinx working class families.14 However, a higher proportion of households of color are helped by the EITC because they make up a smaller percentage of our current population. Another analysis estimates that, overall, average state EITCs for non-White or Latinx-headed households are $120 higher than, and boost more families out of poverty than, EITCs for White, non-Latinx households.15

The Positive, Long-Lasting Benefits the Cost-of-Living Refund Has on Children

Our state EITC, in combination with the federal EITC, has long-lasting positive impacts on the lives of children in families who receive it, and it helps these children into adulthood. In addition to helping pull families, including children, above the poverty line, the EITC also helps improve child health from the start—by improving maternal health and prenatal care and reducing low-birthweight and premature births. Multiple studies have also found that young children in households that receive an income boost from the EITC do better and go farther in school, and ultimately the EITC increases the chances of students being able to attend and/or afford college. Children in families receiving the EITC also tend to go on to earn more as adults. This income boost is especially important for kids of color who have poverty rates two to three times higher than rates for White children. The Cost-of-Living Refund would have the same—if not a larger—impact on kids in our state as more families would qualify for larger credits.

Boost to the Local Economy

Many workers earning low to moderate wages still struggle to pay for basic necessities, like housing, food, transportation costs or child care, let alone get ahead or pay down debt. The income boost of our current federal and state EITCs help families make ends meet. Because our current credit is refundable, this is money that is spent in the local economies, and without the EITC likely would not be spent. Even with a credit as small as 6%, in 2016, up to $114 million was put back into local economies by virtue of the EITC.

The Cost-of-Living Refund would grow this local impact. The Cost-of-Living Refund would provide a basic credit of $1,200 or up to 50% of the federal EITC. Under current law, a family earning a low income with three or more kids receives a state EITC of up to $393; the Cost-of-Living Refund would increase this credit to up to $3,279. Currently, single workers not raising children in their own homes either receive no federal or state EITC, or receive a very small one; the Cost-of-Living Refund would allow these workers not raising children in their own homes to receive a credit of up to $1,200. This would put more than $2 billion back into the local economies, as recipients use the credits to pay for basic needs they otherwise wouldn’t be able to afford.

V. MODERNIZING AND ENHANCING OUR EARNED INCOME TAX CREDIT

Michigan thrives when all of its residents thrive. Unfortunately, many Michiganders continue to struggle and be left behind by our growing economy. Our current EITC is a proven-effective anti-poverty tool that encourages work and helps boost local economies. However, it could go farther, and the Cost-of-Living Refund makes some key improvements on the credit to help more families and provide them larger credits.

More families would qualify for the Cost-of-Living Refund than currently qualify for our state Earned Income Tax Credit due to increases in income limits. Currently, income limits for our state EITC are set by the federal tax code, and these depend on whether the taxpayer is married and how many children he or she has. For example, for tax year 2019 a single worker without kids could only make $15,570, which is a little over poverty levels, and a married couple with three kids could make up to $55,952 to receive the credit. This leaves out many families who still struggle to make ends meet.

The Cost-of-Living Refund recognizes that the EITC income limits are outdated for our current economy. Under the proposal, households with children could make up to $75,000, and childless households up to $37,500, and still qualify for the credit.

The Cost-of-Living Refund extends the credit to adults without children and noncustodial parents. Childless adults currently only receive a very small credit ($32 state credit) or no credit at all. This results in many workers not raising children in their own homes workers being taxed into or deeper into poverty by federal and state tax codes. The Cost-of-Living Refund eliminates age limitations on the credit so that young workers just starting their careers qualify for a credit. This, in addition to the direct increase in the credit amount, allows childless adults, including noncustodial parents who still help raise their children, to qualify for a bigger income boost.

The credit recognizes the important contributions of caregivers and students. Because our current Earned Income Tax Credit requires earned income through employment or self-employment, students and caregivers often do not receive a credit. Under the Cost-of-Living Refund, people attending college half time or caring for a child under 6 or an elderly or disabled relative will receive a basic credit even if they have little to no earned income.

In Michigan, many families face the difficult decision to place a child into child care in order to work. Child care has been and will continue to be a significant expense for working Michigan families. According to recent data, a married family with two kids, an infant and a 4-year-old, in center-based care will spend $19,281 annually for child care. This could end up taking up more than 22% of the family’s annual income, and more than 75% of the income of a married couple with two kids at the poverty line.16 Because of this high cost, families often make the hard decision to leave the workforce and care for a child.

Similar decisions are made when adults need to care for an aging parent or disabled relative. Michigan’s population is aging; recent analysis estimates that Michiganders over 65 will outnumber children under 18 by 2025.17 There are care facilities available, but they are expensive. Individuals can access Medicaid for assistance in covering the cost of certain care, including long-term care, but rules require a person to spend down his or her assets in order to qualify, leaving very little money to live on. The Cost-of-Living Refund recognizes that families may make decisions to stay home and care for a child or elderly or disabled relative and allows them to qualify for the credit.

No one disputes the importance of higher education. Many of Michigan’s top-paying jobs require a certification or degree above and beyond a high school diploma or GED. Poverty rates also fall as higher education attainment is achieved; in adults 25 or older, nearly 30% of people with less than a high school diploma fall into poverty, while only 4.5% of those who reach a bachelor’s degree or higher were in poverty in 2017. However, the cost of starting at a community college or a four-year university is often a barrier, or students must take hefty student loans to attend. Under the Cost-of-Living Refund, students from families with low incomes attending school at least half time would qualify for the credit, even if they don’t have any earned income.

No one disputes the importance of higher education. Many of Michigan’s top-paying jobs require a certification or degree above and beyond a high school diploma or GED. Poverty rates also fall as higher education attainment is achieved; in adults 25 or older, nearly 30% of people with less than a high school diploma fall into poverty, while only 4.5% of those who reach a bachelor’s degree or higher were in poverty in 2017. However, the cost of starting at a community college or a four-year university is often a barrier, or students must take hefty student loans to attend. Under the Cost-of-Living Refund, students from families with low incomes attending school at least half time would qualify for the credit, even if they don’t have any earned income.

The Cost-of-Living Refund gives a much-needed boost to incomes through a significantly larger credit. Currently, Michigan’s Earned Income Tax Credit is worth 6% of the federal credit. This means that, for tax year 2019, childless taxpayers can only receive up to $32 in state credits; taxpayers with one child could see up to $212; with two children could see up to $350; and taxpayers with three or more children could receive a credit worth up to $393. The state credit currently averages $150. The Cost-of-Living Refund would instead provide a basic credit of $1,200 or 50% of the federal credit, providing a significant boost to families’ after-tax incomes.

This proposal would be paid for by raising tax rates on high-income earners, helping right-size Michigan’s upside-down tax code. Michigan has been experiencing tight budgets over the last several years. Lawmakers have decided to dedicate revenue growth to existing needs, resulting in tough decisions in other budget areas. Additionally, the Legislature has often opted to create future tax cuts instead of making the tough decision to raise revenues. This has resulted in a dwindling General Fund—adjusted for inflation, current general fund revenue levels are below 1968 levels, the year our income tax was first in effect—and total state revenues well below our constitutional revenue limitation. Instead of attempting to work within the confines of our current budget, we propose paying for the tax credit by eliminating the constitutional requirement for a flat tax and implementing a graduated income tax, levying higher tax rates on incomes above $250,000.

This proposal would be paid for by raising tax rates on high-income earners, helping right-size Michigan’s upside-down tax code. Michigan has been experiencing tight budgets over the last several years. Lawmakers have decided to dedicate revenue growth to existing needs, resulting in tough decisions in other budget areas. Additionally, the Legislature has often opted to create future tax cuts instead of making the tough decision to raise revenues. This has resulted in a dwindling General Fund—adjusted for inflation, current general fund revenue levels are below 1968 levels, the year our income tax was first in effect—and total state revenues well below our constitutional revenue limitation. Instead of attempting to work within the confines of our current budget, we propose paying for the tax credit by eliminating the constitutional requirement for a flat tax and implementing a graduated income tax, levying higher tax rates on incomes above $250,000.

This would help right-size our upside-down tax code. Currently, taxpayers with the lowest incomes pay the highest share of their incomes in state and local taxes (10.4% of their income goes to state and local taxes) while taxpayers in the top 1% pay the lowest share (6.2%). By increasing marginal tax rates on incomes over $250,000 and providing a generous tax credit to over one-third of Michigan families, our tax code would look a lot fairer.

Policymakers should to consider whether it makes sense to continue paying the credit in a lump sum or if providing monthly distributions would provide more help to Michigan families struggling to make ends meet every month. Many EITC recipients use their lump-sum payments to help pay down debt or pay deferred expenses, such as car repairs. The fact that current federal and state EITCs are paid out in a lump sum may make it difficult for these families to use their credits for monthly expenses—like housing or food—even though their wages often do not cover the full cost of those expenses. While some families prefer receiving the one-time bump in incomes to make larger purchases, like replacing an old and failing appliance or making car repairs or getting new tires, it may be worthwhile to determine whether paying a family’s anticipated credit in monthly amounts would help them be more able to pay monthly expenses instead of taking on debt.

Endnotes

- “Policy Basics: The Earned Income Tax Credit,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-the-earned-income-tax-credit.

- Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Statistics for Tax Returns with EITC, Calendar Half Year Report, June 2018.

- Wesley Tharpe, “Raising State Income Tax Rates at the Top a Sensible Way to Fund Key Investments,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/raising-state-income-tax-rates-at-the-top-a-sensible-way-to-fund-key.

- Cristobal Young, Charles Varner, Ithai Z. Lurie, Richard Prisinzando, “Millionaire Migration and Taxation of the Elite: Evidence from Administrative Data,” American Sociological Review, Vol. 81(3) 421-446, 2016, https://web.stanford.edu/~cy10/public/Jun16ASRFeature.pdf .

- Ibid.

- Estelle Somneiller and Mark Price, “The New Gilded Age: Income Inequality in the U.S. by State, Metropolitan Area, and County,” Economic Policy Institute, July 2018, https://www.epi.org/multimedia/unequal-states-of-america/#/Michigan.

- Please note, this was not what the original petition backers wanted, which was a $12 per hour by 2022. Instead of letting the voters decide, the Legislature enacted the ballot language and then amended it.

- Erica Williams and Samantha Waxman, “State Earned Income Tax Credits and Minimum Wages Work Best Together,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-earned-income-tax-credits-and-minimum-wages-work-best-together.

- “ALICE in Michigan: A Financial Hardship Study,” Michigan Association of United Ways, 2019, https://www.uwmich.org/alice .

- Ibid.

- 2026 State of Michigan Career Outlook, Bureau of Labor Market Information and Strategic Initiatives, Department of Technology, Management and Budget, http://milmi.org/Portals/198/publications/CareerOutlook_2026.pdf?ver=2018-08-06-100602-650.

- Hot 50: Michigan’s High-Demand, High-Wage Careers, Michigan’s Job Outlook through 2026, Bureau of Labor Market Information and Strategic Initiatives, Department of Technology, Management and Budget, http://milmi.org/Portals/198/publications/Hot_50_Brochure_2026.pdf?ver=2018-10-30-084757-123.

- Peter Ruark, “Back to school report: Rising tuition and weak state funding and financial aid create more student debt,” Michigan League for Public Policy, 2016, https://mlpp.org/back-to-school-report-rising-tuition-and-weak-financial-aid-create-more-student-debt/.

- Cecile Murray and Elizabeth Kneebone, “The Earned Income Tax Credit and the white working class,” Brookings Institution, April 18, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2017/04/18/the-earned-income-tax-credit-and-the-white-working-class/.

- Douglas J. Gagnon, Marybeth J. Mattingly, and Andrew Schaefer, “State EITC Programs Provide Important Relief to Families in Need,” University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy, Carsey Research National Issue Brief #115, Winter 2017, https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1295&context=carsey .

- The US and the High Cost of Child Care:2018, Child Care Aware of America, http://usa.childcareaware.org/advocacy-public-policy/resources/research/costofcare/.

- Bill Laitner, “Michigan is aging faster than the rest of the U.S.—here’s why,” Detroit Free Press, June 8, 2018, https://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/wayne/2018/06/08/michiganders-100-years-old-senior-tide-coming-first-michigan-2025/675828002/.

[types field=’download-link’ target=’_blank’][/types]

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders.

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders. Jacob Kaplan

Jacob Kaplan

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.  Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget.

Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget. Donald Stuckey

Donald Stuckey  Patrick Schaefer

Patrick Schaefer Alexandra Stamm

Alexandra Stamm  Amari Fuller

Amari Fuller

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.