The 2018 budget includes several investments that address pervasive, unacceptable and avoidable barriers to opportunity for many of the state’s children of color, but a much more intentional effort is needed to overcome long-standing inequities that can be traced to public policies in Lansing and nationwide. State budgets are not “colorblind”—even if their disproportionate impact is unintended.

The annual budget has been aptly described as the best measure of the state’s priorities. Each year, lawmakers must distribute state funds in ways that meet basic needs, maintain critical infrastructure, ensure basic health and safety and invest in the future—most critically for children.

How lawmakers divide up the state budget has the potential to help or hinder children’s development and ability to learn, create or limit economic opportunities for families and communities, and protect or threaten public health and safety.

Through its Kids Count program, the League documents outcomes for children and their families, including racial and ethnic disparities. The League has as a primary goal equity for all children and knows that to get there, policymakers and the public must first understand and acknowledge that inequities exist.

Job one is to educate ourselves and our community leaders, which is only possible if there is adequate data to inform budget and policy decisions. There is a tradition of close and ongoing monitoring of economic data including, for example, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Our children deserve the same.

But documenting indefensible outcomes for children of color and their families is not enough. For every negative outcome there is a backstory—a history of inequality based on race, income and place. Michiganians share a value of opportunity for all children, but the data show us that good intentions have not always resulted in good outcomes.

Michigan cannot afford to take lightly the undeniable obstacles being faced by its growing number of children of color. To move from indexing inequality to making change, lawmakers and other leaders must be intentional in facing the true impact of the policy and budget decisions they make on children, families and communities of color; they must support investments that help remove the long-standing structural barriers to opportunity for all children.

ECONOMIC SECURITY

Differences in economic security and opportunity are at the core of racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes for families and their children. The systemic barriers to economic security include housing discrimination, the historical impact of redlining on homeownership, segregation in public schools, differences in educational quality and opportunity, racial discrimination in the workplace, and inequities in the ability to accumulate assets and wealth.

These systemic barriers have their roots in historical racism and discrimination, but persist today in part because of budgets and other public policies that do not recognize the extra resources required to overcome the cumulative effects of inequities based on race and ethnicity. The data are clear. Families and children of color are being held back from many of the traditional pathways to economic opportunity and security. Given the growing diversity of the state, this threatens the economic growth all state residents depend on.

How Michigan Children and Families Are Faring: Inequities in economic opportunity have a strong and well-documented impact on the next generation of Michiganians. Children who grow up in poverty are more likely to have poor nutrition, live in homes and neighborhoods where they are exposed to environmental toxins, and have untreated health conditions. Their parents struggle to provide the enrichment activities children need in the earliest years of life, including books, toys, activities and high-quality early learning opportunities. Further, the economic stresses faced by parents are linked to depression and anxiety, which raise the risk of substance use disorders.1

How Michigan Children and Families Are Faring: Inequities in economic opportunity have a strong and well-documented impact on the next generation of Michiganians. Children who grow up in poverty are more likely to have poor nutrition, live in homes and neighborhoods where they are exposed to environmental toxins, and have untreated health conditions. Their parents struggle to provide the enrichment activities children need in the earliest years of life, including books, toys, activities and high-quality early learning opportunities. Further, the economic stresses faced by parents are linked to depression and anxiety, which raise the risk of substance use disorders.1

The rising economy has not lifted all boats. Lower unemployment rates in Michigan have not translated into secure employment for all families. More than half of the state’s African-American children live in families where no parent has full-time, year-round employment, along with 40% of Hispanic/Latino children or those of two or more races.

Children of color are two to three times more likely to live in poverty. Despite overall improvements in the state’s economy, the number of children living in poverty has remained stubbornly high, particularly for children of color. More than 1 of every 5 children in the state lives in poverty, with child poverty rising from 19% in 2007 to 22% in 2015. Most unacceptable is the fact that nearly one-third of Latino children or children of two or more races lives in poverty, as do half of African-American children.

Children of color are two to three times more likely to live in poverty. Despite overall improvements in the state’s economy, the number of children living in poverty has remained stubbornly high, particularly for children of color. More than 1 of every 5 children in the state lives in poverty, with child poverty rising from 19% in 2007 to 22% in 2015. Most unacceptable is the fact that nearly one-third of Latino children or children of two or more races lives in poverty, as do half of African-American children.

Even larger numbers of children are living in homes where it is difficult to make ends meet. The League has estimated that a single parent with two children under age 5 would need to earn approximately $47,000 per year to cover the costs of housing, child care, food, transportation and other personal expenses.2 Almost 3 of every 4 African-American children in Michigan, along with 2 of every 3 Latino children, live in households with incomes of 200% of poverty or less (approximately $48,000 per year).

Many children face the possibility of not having enough food. In 2014, 338,000 Michigan children lived in households facing the possibility of not having adequate food. And despite overall economic growth in Michigan, almost half of the state’s children are eligible for free or reduced-price meals in school. African-American and Latino families experience higher levels of food insecurity, a dynamic that has continued in the aftermath of the Great Recession.3

Housing is unaffordable for many families. Nearly half of African-American children, and over one-third of Latino children or those of two or more races, live in homes where housing costs are particularly burdensome, representing more than 30% of monthly income.

Housing is unaffordable for many families. Nearly half of African-American children, and over one-third of Latino children or those of two or more races, live in homes where housing costs are particularly burdensome, representing more than 30% of monthly income.

Budget Decisions Affecting Economic Security: Despite continuing high rates of poverty and economic insecurity for the state’s children, and particularly for children of color, state funding for programs to ensure that children’s basic needs are met has plummeted. The result has been continuing struggles for families with children, as well as the shrinking of funding to low-income communities.

For example, in the 10 Michigan counties with the highest percentages of children of color, funding for income assistance fell by between 53% and 81% in the five years from 2010 to 2015. Funding for child care subsidies to ensure that parents with low-wage jobs can work to support their children fell by between 20% and 56%. For 2018, lawmakers:

Expanded funding for food assistance, but more work needs to be done to ensure access to healthy food. The budget for the upcoming fiscal year includes:

Expanded funding for food assistance, but more work needs to be done to ensure access to healthy food. The budget for the upcoming fiscal year includes:

- A continuation of the “heat and eat” policy. The final budget authorizes funding for the “heat and eat” policy, which increases food assistance for nearly 340,000 Michigan residents. Four of every 10 recipients of food assistance are children. Given income inequalities based on race and place in Michigan, this expansion is likely to improve the health of thousands of children of color as well as their parents.

- A small investment in access to healthy food. Federally-funded food assistance does not ensure access to healthy food. The 2018 state budget includes: (1) $750,000 in the current budget year and $380,000 in the 2018 budget to match a three-year federal grant to encourage the use of food assistance dollars for healthy foods; (2) $500,000 ($250,000 in state funds) for the purchase of wireless equipment by farmers markets so families can use their Bridge Cards to purchase healthy food; and (3) an additional $10 million in federal funding for nutrition education programs for persons receiving food assistance. The Legislature failed to fund a Michigan Corner Store Initiative that was intended to provide grants to small food retailers to increase the availability of fresh and nutritious foods in low- and moderate-income areas.

Accessing healthy food is a challenge for many families, particularly those living in urban communities of color or in more remote rural areas. With few grocery stores in urban areas, many families live in “food deserts,” requiring them to travel to find healthier foods. Fast-food restaurants and other businesses that sell processed foods with little nutritional value have replaced food retailers in these communities. A national study found that low-income, urban neighborhoods of color have the least availability of grocery stores and supermarkets compared with both low- and high-income White communities.4

The lack of access to healthy foods can have long-term effects on children of color concentrated in urban areas. Living closer to sources of healthy food has been shown to decrease the risk of obesity and diet-related illness. In Michigan, 1 in 3 children is overweight or obese, and 70-80% of obese children become obese adults who are more likely to suffer from heart disease, diabetes and some cancers. This comes at a cost to the state: Michigan is expected to spend $12.5 billion on obesity-related health care costs in 2018.5

Continued to endorse policies that have led to the decline in funding for income and family support programs. The 2018 budget fails to reverse the state’s dramatic disinvestment in income support programs for families with children, which has pushed the number of Michigan families receiving Family Independence Program (FIP) benefits to its lowest level since 1957. The dismantling of this basic needs program has had a disproportionate effect on children of color, whose parents have been less able to take advantage of economic recovery and job growth in the state. More than 70% of the recipients of FIP are children—many of them very young children of color.

For 2018, the Michigan Legislature:

- Rejected a small increase in the clothing allowance that was proposed by the governor. The Legislature ultimately rejected a small increase in the school clothing allowance for children in families receiving income assistance through the FIP. The clothing allowance remains at $140 per child per year.

- Expanded the Pathways to Potential program. The Pathways to Potential program, which places “success coaches” in schools to identify barriers faced by students and their families and makes appropriate referrals for services, is in 259 schools in 34 counties. The final 2018 budget increased the program by a total of $4.9 million. Pathways to Potential is intended to work with families through their children’s schools and in conjunction with community partners. It is a promising model for a two-generational approach to the barriers facing many families of color and parents with low incomes.

- Increased support for homeless shelters. The 2018 budget increases the rate paid to homeless shelters from $12 to $16 per person, per night at a cost of $3.7 million. Because nearly half of African-American children—and more than a third of Latino children or those of two races—are living in homes where housing costs consume a significant portion of the family income, homelessness is a looming threat for many children of color. An estimated 100,000 people in Michigan are either homeless or imminently at risk of homelessness, and families with children make up half of the homeless population. More than half of people who are homeless in the state are African-American.6

Expanded funding for child care services that parents need to find and keep jobs that can help them support their children. The Legislature increased funding for child care by $19.4 million (including $8.4 million in state funds) to increase reimbursement rates to child care providers, as well as $5.5 million to raise the eligibility threshold for a child care subsidy from 125% of poverty to 130%.

Child care costs are some of the largest that families face, rivaling housing and even the price of a year of college. Without assistance, many parents are either forced out of the workforce or required to rely on relatives or neighbors who may be facing health problems or other hardships of their own. A family with wages of 150% of poverty (approximately $29,000 per year for a family of three in 2016) would need to spend over 60% of its income to place two children in a child care center; a family child care home would consume nearly half of the family’s income.

The median family income for an African-American family with children in Michigan in 2015 was $27,200—two and a half times less than the median income for non-Hispanic White families at $71,600.7 The high cost of child care perpetuates disparities in income as more families of color are unable to afford the child care they need to work. High child care costs relative to family income also further hamper children’s development by increasing the likelihood that children of color will be placed in lower quality child care settings.

HEALTH

How Michigan Children and Families Are Faring: Michigan has a history of effectively covering children through the Medicaid and MIChild programs, with the percentage of children uninsured consistently below the national average. With the Affordable Care Act, the rate of uninsured children dropped even further. However, the state’s children of color still have less access to needed physical and mental healthcare, are more frequently born underweight and die before their first birthdays, and face environmental injustices related to exposure to toxins in their homes and neighborhoods.

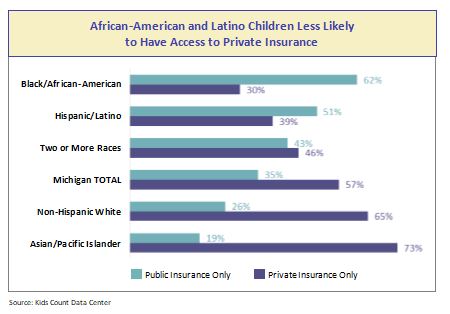

Fewer children of color have access to private health insurance. As a result of historical and current barriers to a high-quality education and career path for many African-American and Latino parents, their children have less access to private health insurance. Two of every 3 African-American children—and half of Latino children—in Michigan rely on public health insurance programs for healthcare coverage. Consequently, improvements in access to comprehensive publicly funded healthcare coverage can significantly improve equity for children.

Fewer children of color have access to private health insurance. As a result of historical and current barriers to a high-quality education and career path for many African-American and Latino parents, their children have less access to private health insurance. Two of every 3 African-American children—and half of Latino children—in Michigan rely on public health insurance programs for healthcare coverage. Consequently, improvements in access to comprehensive publicly funded healthcare coverage can significantly improve equity for children.

The number of uninsured children continued to fall after adoption of the Affordable Care Act, and more women had access to healthcare prior to pregnancy, improving birth outcomes. Nationwide, the rate of uninsured children fell from 7.1% to 4.8% between 2013 and 2015—the largest two-year decline on record, which coincided with the implementation of most provisions of the Affordable Care Act.8 Michigan also experienced improvements in coverage, with the number of uninsured children falling from 90,000 in 2013 to 68,000 in 2015. Coverage for parents also improved, and research shows that extending new coverage to parents results in more children obtaining coverage.9

The number of uninsured children continued to fall after adoption of the Affordable Care Act, and more women had access to healthcare prior to pregnancy, improving birth outcomes. Nationwide, the rate of uninsured children fell from 7.1% to 4.8% between 2013 and 2015—the largest two-year decline on record, which coincided with the implementation of most provisions of the Affordable Care Act.8 Michigan also experienced improvements in coverage, with the number of uninsured children falling from 90,000 in 2013 to 68,000 in 2015. Coverage for parents also improved, and research shows that extending new coverage to parents results in more children obtaining coverage.9

Mental health services for parents and children are still insufficient. It is estimated that 1 of every 5 Michigan children (410,000) has one or more emotional, behavioral or developmental conditions.10 Approximately 50,000 are served by Michigan’s public community mental health system.11

Mental health services for parents and children are still insufficient. It is estimated that 1 of every 5 Michigan children (410,000) has one or more emotional, behavioral or developmental conditions.10 Approximately 50,000 are served by Michigan’s public community mental health system.11

In addition, there is strong evidence that maternal depression can have a severe impact on both mother and child, ultimately affecting children’s growth and development, and there has been an increase in the suicide rate for both White and African-American youths.12

Fewer women of color are receiving early prenatal care and more of their children do not survive to celebrate their first birthdays. In its recent Kids Count Right Start report, the League documented racial and ethnic disparities in maternal and child health. Among the problems facing mothers and their babies are maternal smoking during pregnancy, preterm births, the lack of access to timely prenatal care and a higher frequency of infants born low-weight.

Fewer women of color are receiving early prenatal care and more of their children do not survive to celebrate their first birthdays. In its recent Kids Count Right Start report, the League documented racial and ethnic disparities in maternal and child health. Among the problems facing mothers and their babies are maternal smoking during pregnancy, preterm births, the lack of access to timely prenatal care and a higher frequency of infants born low-weight.

Of great concern is that African-American, Hispanic and Middle Eastern infants are much more likely to die before their first birthdays. The infants most at risk are those born prematurely with low birthweights, babies born to mothers with low incomes or covered by Medicaid, and babies that are the result of unintended pregnancies.

The reality is that access to healthcare coverage—which has expanded—does not ensure that pregnant women are able to find a provider within a reasonable distance from their home who will accept them as patients; or overcome the many barriers to adequate care, including provider bias or language and transportation issues. As a result of these barriers, African-American and Latina mothers are much more likely to receive late or no prenatal care, and their children are more likely to be born too early and too small.

In low-income communities and older urban areas where children of color are more concentrated, the rates of exposure to environmental hazards like lead are higher. The lead poisoning public health disaster in Flint put Michigan in the national spotlight, and brought to the public’s attention the disastrous effects of the state’s failure to invest in basic infrastructure and public health services. But the threats to children from lead and other environmental hazards are not limited to Flint. In the 2016 budget year, over 150,000 children under the age of 7 were tested for lead exposure, and approximately 5,500 (3.6%) had elevated blood lead levels.13

While the number of children tested and found to be exposed to lead was higher in the city of Detroit than any county in Michigan, the counties with the highest percentage of children under age 6 with elevated blood lead levels in 2015 were Lenawee, Mason and Kent.14 Data from Kent County show that African-American and Hispanic children ages 0-5 in the county are more than twice as likely to be exposed to harmful levels of lead.15

While the number of children tested and found to be exposed to lead was higher in the city of Detroit than any county in Michigan, the counties with the highest percentage of children under age 6 with elevated blood lead levels in 2015 were Lenawee, Mason and Kent.14 Data from Kent County show that African-American and Hispanic children ages 0-5 in the county are more than twice as likely to be exposed to harmful levels of lead.15

Budget Decisions Affecting Children’s Health: While Michigan continues to invest in healthcare coverage for children and families, access to physical and mental healthcare for families with low incomes and children of color remains a problem. In addition, Michigan has failed to invest adequately in the public health infrastructure needed to ensure that all children are born healthy, that pregnant women and new mothers—particularly those of color who are now underserved—have access to healthcare and adequate supports in the difficult job of parenting, and that children are not subject to the types of environmental injustices that made Flint’s lead exposure crisis a national disgrace. The Michigan Legislature made some significant investments to support the health of Michigan’s children, but missed several other opportunities to better care for kids.

Continued funding for Medicaid and the Healthy Michigan Plan. Continued investments in publicly funded health insurance options are critical to improving equity, in part because of discrimination in the workplace that has resulted in very low private coverage for children of color and their families. For 2018, lawmakers:

- Supported the Healthy Michigan Plan with both federal and state funding. The plan provides healthcare coverage to about 650,000 people with low incomes, but the potential remains for congressional action to gut the program. Increased state funding is required because the federal match, which is at 95% in the 2017 calendar year, will drop annually until it reaches 90% in 2020 and subsequent years.16

- Provided funding for Medicaid services for pregnant women and children. Children represent 39% of all Medicaid recipients, but account for only 20% of Medicaid expenditures.17 In July of 2017, 391,129 pregnant women and children under the age of 19 were covered by Medicaid.18

- Established pilot projects to integrate the administration of behavioral health services. The Legislature moved forward on the controversial integration of physical and behavioral health in Michigan by authorizing a pilot project for full integration in Kent County, as well as three demonstration projects that integrate financing. The stated goal is to test how the state can improve outcomes and efficiencies in serving persons receiving behavioral health services.

Provided a small funding increase to address the need for transportation for families seeking healthcare. The governor had proposed an expansion of the current transportation programs in Macomb, Oakland and Wayne counties, where there are contracts for coordinating transportation for persons needing nonemergency care. In other counties, families must rely on local Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) workers—who are already stretched thin—to coordinate transportation. The final budget includes $1.4 million to expand the use of local public transportation.

Children and families of color are more likely to be covered by public health insurance programs like Medicaid and the Healthy Michigan Plan, but access remains a problem—in part because of difficulty finding providers within a reasonable distance from home, as well as less access to reliable transportation.

Continued to invest in efforts to address the Flint lead exposure crisis. Michigan’s failure to invest in the public health infrastructure needed to prevent lead poisoning has come at a very high human and fiscal cost. Exposure to lead can thwart a child’s growth and development in ways that can last into adulthood, so the true costs are incalculable. However, it is estimated that the state will spend $478 million ($246 million in state funds) on the crisis between the 2016 and 2018 budget years.19 The bulk of those funds were appropriated to the Department of Environmental Quality ($158 million) and the Department of Health and Human Services ($143 million). For 2018, lawmakers:

- Decreased the state portion of the costs of services to address the Flint water crisis from $43.7 million this year to $41.5 in 2018.20 Within the DHHS, funds are used for health services, food and nutrition services (including Double-Up Food Bucks), case management, education and outreach, child and adolescent health centers and schools, lead testing and abatement, water filters, and lead testing at local food service establishments.21

- Included $1.25 million to begin implementing the recommendations of the Child Lead Poisoning Elimination Board. The Board was created by the governor in 2016 and made 80 recommendations for state action.

- Approved $815,000 to prevent dangerous chemical vapor intrusions. The Legislature appropriated the funds to continue a new response program for the intrusion of volatile chemical vapors into homes and buildings.

Continued underfunding of public health services. One of the major goals of Michigan’s public health system is to provide services that address the health issues of populations with high needs in the state, including maternal and children’s health services. Services are provided through the state’s 45 local public health departments. Funding for public health has been relatively flat since 2007, with increases primarily in federal grants for lead abatement and state health system innovations. Funding to local public health departments is approximately the same as it was in 2004.22 For 2018, lawmakers:

- Added legislative intent that more be done to encourage access to prenatal care. As of 2014, there were 5.1 obstetrician/gynecologists (ob-gyns) for every 10,000 Michigan women ages 15 to 25, which is below the national average, and 28 of Michigan’s 83 counties did not have any ob-gyns—furthering the likelihood that families with fewer resources are unable to find care.23 Because women with low incomes and women of color have less access to prenatal care, initiatives to improve access can also improve equity and outcomes for newborns.

The 2018 budget adds language requiring the DHHS to engage in outreach activities that will encourage early, continuous and routine prenatal care, and promote policies and practices that improve access to prenatal and obstetrical care. Unfortunately, this budget language is not connected to adequate funding.

- Eliminated a health innovation mini-grant program. The Legislature eliminated the $1 million Health Innovation Program that provided mini-grants to a range of community agencies. Among the current grants are efforts to provide housing for homeless people being discharged from the hospital; increase access to healthy foods for teens, parents and persons with chronic illnesses; add physical activity to summer feeding programs; train students of color to become Certified Nurse Aides or in other allied health careers; promote breastfeeding by African-American women through peer mentoring; and link people in supportive housing to primary healthcare services.

FAMILY AND COMMUNITY

A long history of racial and economic inequality, along with racial segregation, have led to gross differences in the resources available in the neighborhoods many Michigan children of color grow up in. Too frequently children of color are living in high-poverty areas where safety is a concern, and access to parks, fresh food, and after-school and other enrichment activities is limited.

In addition, the barriers and economic stresses facing parents in lower-income communities of color often affect their ability to provide the support and care their children need. High rates of maternal depression with limited access to mental health and substance use disorder services, the scarcity of jobs providing a living wage, problems finding safe and reliable child care, inadequate transportation and substandard housing are all examples of the stresses facing parents.

How Michigan Children and Families Are Faring:

African-American children are eight times more likely to live in high-poverty communities. More than 1 in 6 children in the state lives in concentrated poverty, or census tracts where the poverty rate is 30% or higher, including more than half of African-American children ages 0-17 (55%), and 29% of Hispanic children and youths. Neighborhoods with concentrated poverty tend to have higher rates of crime and violence, higher unemployment rates with fewer job opportunities, and poor health outcomes with increased toxic stress for children and their families.24

African-American children are eight times more likely to live in high-poverty communities. More than 1 in 6 children in the state lives in concentrated poverty, or census tracts where the poverty rate is 30% or higher, including more than half of African-American children ages 0-17 (55%), and 29% of Hispanic children and youths. Neighborhoods with concentrated poverty tend to have higher rates of crime and violence, higher unemployment rates with fewer job opportunities, and poor health outcomes with increased toxic stress for children and their families.24

Four of every 10 African-American children in Michigan have been exposed to two or more adverse childhood experiences, including frequent economic hardship; parental divorce or separation; parental death; parental incarceration; family violence; neighborhood violence; living with someone who is mentally ill, suicidal or has a substance use disorder; or facing racial bias. Research shows that these adverse childhood experiences can have long-term effects on children, including poor health as adults, learning and behavioral issues, and adolescent pregnancy.

African-American children and youths are much more likely to live in unsafe neighborhoods. More than one-third (35%) of African-American children live in neighborhoods that their parents or caretakers describe as sometimes or rarely safe, compared to 26% of Latino children and just 7% of non-Hispanic White children.25

Children of color are overrepresented in the state’s child welfare system. At nearly every point in the child welfare system, children of color have historically been over-represented, although changes in data collection systems at the state level have resulted in data gaps related to outcomes for children of color.26

In 2014, the Michigan Race Equity Coalition found that children of color are more likely to live in families investigated for abuse or neglect, are more likely to be removed from their homes than White children, and are twice as likely to stay in foster care until they age out. Given the known relationship between the lack of a permanent home and a heightened risk of homelessness, unemployment, incarceration, substance abuse and other negative outcomes, the overrepresentation of children of color has dire consequences.27

Contributing to the problem is the high level of family stress resulting from the lack of economic opportunities for families of color and related high child poverty rates. Of the confirmed victims of child maltreatment, approximately 8 in 10 show evidence of neglect—including conditions related to poverty such as a failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter or medical care.

Budget Decisions Affecting Families and Communities: Michigan lacks a comprehensive strategy to address poverty through an interdepartmental, two-generational approach that focuses on the impact of income and racial inequities that have limited opportunities for many families and children based on race, ethnicity and geography. In fact, investments in communities have lagged and supports to families are inadequate. For 2018, lawmakers:

Failed to adequately fund revenue sharing payments to cities, villages and townships. The 2018 budget includes $6.2 million in one-time funding for cities, villages and townships. This follows years of budgets that did not include the payments to local communities that are statutorily required. State budget and policy changes have reduced the number of cities, villages and townships eligible for state revenue sharing payments. In 2016, only 587 out of 1,772 Michigan cities, villages and townships received payments; in 2001, all were eligible. In addition, the portion of revenue sharing that is not provided through the Michigan Constitution (previously known as “statutory revenue sharing”) has declined almost 70% since the 1998 budget year, and current payments are at only 30% of the statutory level.28

Provided a small increase for social services offered by multicultural organizations. The 2018 budget expands funding for social services programs for a range of organizations, including the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services (ACCESS), the Arab Chaldean Council, the Jewish Federation and the Chaldean Community Foundation. Funding for the programs is currently at $13.3 million.

Provided funding for child protective services and foster care, but continued to underfund services that could prevent child abuse and neglect. The Legislature continues to provide funding for the child welfare staffing and services needed to move children out of the foster care system and into permanent homes—as required by a settlement agreement stemming from a lawsuit against the state for failures in its child welfare system. The lawsuit does not address the disproportionate representation of children of color in the state’s foster care system or require additional efforts to prevent child abuse and neglect. For 2018, lawmakers:

- Increased rates paid to private agencies for foster and residential care for abused and neglected children. The 2018 budget includes $14.2 million for rate increases for providers of foster care, independent living, family reunification and residential services.

- Expanded funding for the recruitment and support of foster families, as well as the Michigan Youth Opportunities Initiative (MYOI). Because children of color are overrepresented in the state’s foster care system and are more likely to age out of foster care as young adults, efforts to find stable, high-quality foster homes, as well as services to improve the transition to independence are critical in reducing inequities. The Legislature approved the governor’s recommendation to spend $3.6 million to support regional resource teams to recruit, train and support foster families, as well as an expansion of the MYOI programs.

- Reduced funding for family preservation. In 2018, family preservation programs will be cut by $6.1 million. The funds were used this year for Parent Partner and family reunification programs in Macomb and Genesee counties and are intended to prevent the need for foster care and reunify children with their families when it is safe to do so.

Programs that help build on family strengths, prevent out-of-home placements of children and facilitate reunification can be of special benefit to families of color and families with low incomes—both of which are overrepresented in the state’s child welfare system. Unfortunately, the state has invested far too little in family preservation and prevention services that could help reduce the stresses families with fewer resources face, and enhance parents’ ability to care for and nurture their children—including access to sufficient income supports needed for stable housing and other basic needs.

EDUCATION

A high-quality education is a vital path to equity for children in Michigan, yet the data show that Michigan has a long way to go. Children of color have less access to high-quality early learning experiences and face barriers throughout the educational system.

How Michigan Children and Families Are Faring:

How Michigan Children and Families Are Faring:

More needs to be done to ensure all children have access to supports that can improve their ability to learn—beginning before birth. Learning begins with a healthy mom and a healthy birth, and is at its peak in the earliest years of life. Michigan has made strides in making sure that 4-year-olds from families with low incomes have access to preschool, but there is no state funded preschool program for 3-year-olds, and funding for services for infants and toddlers and their parents are grossly underfunded.

Statewide, access to a preschool education is more limited for Latino children, with 59% of 3- and 4-year-olds not in preschool.29 The research is strong. Access to high-quality early learning and family support programs—beginning at birth—is one of the best tools we have for overcoming disparities in achievement and ultimately in earnings.

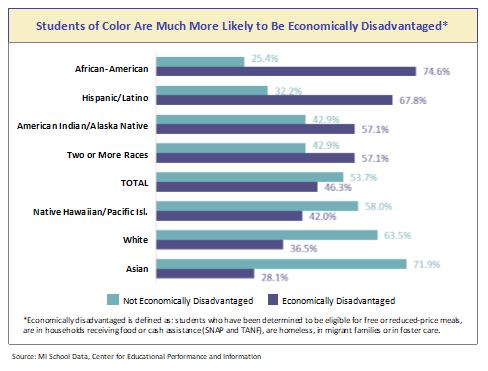

Students of color are more likely to be in families with low incomes. Because of the indisputable connection between family income and student achievement, the high level of economic disadvantage faced by children of color is a stark reminder of broader social issues that result in inequities in educational achievement.

Three of every 4 African-American students and two-thirds of Latino students in the state are considered economically disadvantaged because they: (1) are eligible for free or reduced-price school meals; (2) are in households receiving cash or food assistance; or (3) are homeless, in migrant families or in foster care.

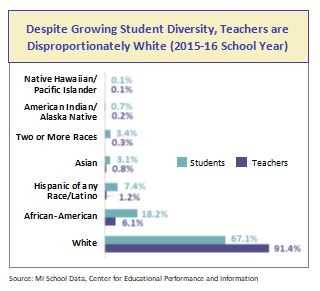

Michigan teachers do not reflect the diversity of their students. There is mounting evidence that having at least one teacher of the same race increases the likelihood of school success, including test scores, attendance and fewer suspensions. A recent study also shows that for African-American students, an African-American teacher in elementary school increases the likelihood that male students will graduate from high school.30

Michigan teachers do not reflect the diversity of their students. There is mounting evidence that having at least one teacher of the same race increases the likelihood of school success, including test scores, attendance and fewer suspensions. A recent study also shows that for African-American students, an African-American teacher in elementary school increases the likelihood that male students will graduate from high school.30

Despite the benefits of teacher diversity, Michigan teachers do not reflect the demographics of their students. In the 2015-16 school year, 67% of Michigan students and 91% of the state’s teachers were White. Nationally, 82% of public school teachers were White in 2011-12, making Michigan’s teaching workforce less diverse than the national average four years earlier.31

Racial and ethnic disparities affect educational out-comes. While there are inequities in educational achievement in all subjects, significant focus has been placed on reading by third grade, including Michigan legislation that allows for retention of students in certain circumstances. In the 2015-16 school year, 20% of African-American students were reading proficiently by third grade, compared to 54% of their White counterparts. More than half (56%) of African-American third-graders would have been subject to retention if the policy had been implemented in 2015-16, compared to only 21% of White students.

Graduation rates vary by race, ethnicity and gender. While the state’s high school dropout rate has been falling, high percentages of children of color are still not graduating, and young men of color are at the highest risk. In the 2015-16 school year, 18% of African-American boys and 11% of African-American girls dropped out of school—significantly above the rates for their White peers at 8% and 6% respectively. Latino youths were approximately twice as likely to drop out of high school as White youths.

Graduation rates vary by race, ethnicity and gender. While the state’s high school dropout rate has been falling, high percentages of children of color are still not graduating, and young men of color are at the highest risk. In the 2015-16 school year, 18% of African-American boys and 11% of African-American girls dropped out of school—significantly above the rates for their White peers at 8% and 6% respectively. Latino youths were approximately twice as likely to drop out of high school as White youths.

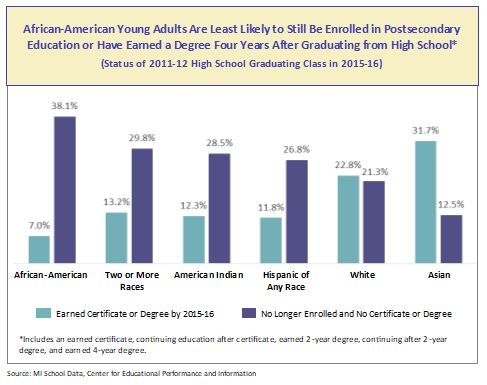

African-American and Latino young adults are less likely to be ready for college after graduating from high school. Reflecting diminished opportunities beginning early in life and accelerating during the school years, only 10% of African-American students and 19% of Latino students met or exceeded the SAT benchmark for college readiness in 2015-16. As a result, African-American and Latino youths are less likely to pursue postsecondary education within six months of graduating and are much more likely to require remedial coursework once in college.

Educational inequities persist, affecting success in college. Even when young men and women of color are able to enter college, financial and other barriers to their continued success remain. Four years after graduating high school and directly entering a postsecondary program, 38% of African-American students are no longer enrolled and have not completed a degree program, and only 7% have completed their degrees. By contrast, 23% of White students completed their postsecondary program in four years.

Budget Decisions Affecting Educational Success: Michigan’s recent investments in early learning and programs for students in high-poverty communities are a good start, but there is more work to be done to overcome persistent and deep disparities in educational opportunities for Michigan children based on income, race and geography. For 2018, state lawmakers:

Budget Decisions Affecting Educational Success: Michigan’s recent investments in early learning and programs for students in high-poverty communities are a good start, but there is more work to be done to overcome persistent and deep disparities in educational opportunities for Michigan children based on income, race and geography. For 2018, state lawmakers:

Increased per-pupil spending with larger increases for districts currently receiving the lowest payments. The Legislature approved an increase of between $60 and $120 per pupil, using a formula that benefits districts with lower payments. Two of every $3 in the School Aid budget are used to support per-pupil payments, which are the primary source of funding for school operations.

After a cut of $470 per pupil in 2010-2012, per-pupil payments to schools have begun to increase, and additional state funds have been used to hold districts harmless from increasing retirement liability costs. Nonetheless, total funding for foundation allowances and other operational costs is still below the 2007 peak.32 Further, in the 10 years between 2007 and 2017, the minimum per-pupil payment increased 6%, while the cost of living increased 12.6%.33

After a cut of $470 per pupil in 2010-2012, per-pupil payments to schools have begun to increase, and additional state funds have been used to hold districts harmless from increasing retirement liability costs. Nonetheless, total funding for foundation allowances and other operational costs is still below the 2007 peak.32 Further, in the 10 years between 2007 and 2017, the minimum per-pupil payment increased 6%, while the cost of living increased 12.6%.33

Increased payments for high school students. The final budget includes $11 million to provide a bonus payment of $25 per pupil in grades nine through 12—recognizing the costs associated with the high school curriculum.

Increased funding for students at risk of educational failure. The Legislature approved an increase of $120 million for the At-Risk School Aid program, bringing total funding to $499 million. The distribution formula for the funds was altered to include “out-of-formula” or “hold-harmless” districts that are not currently eligible even though they may have high numbers of children living in poverty, but payments to those districts were capped at 30%. Finally, the definition of “at risk” was changed to include pupils eligible for free and reduced-price meals; those receiving income or food assistance; or those who are homeless, in migrant families or in foster care. The changes support an increase in eligible pupils of 131,000 due to expansions in both the number of eligible school districts and broader pupil eligibility.34

The At-Risk School Aid program is the state’s best vehicle for addressing the educational challenges faced by children who are exposed to the stresses of poverty and has the potential to help improve equity for children of color. After a decade of flat spending, increases in the current and upcoming budget years have expanded the program by over 60%—a positive and needed move in the right direction.

Failed to provide sufficient funding to address racial and ethnic disparities in early literacy. Proficient reading by the end of third grade is critical. A child’s ability to read by third grade is an important predictor of whether or not he or she will drop out of school, find regular employment or even end up incarcerated. By the time children enter kindergarten, there are already large gaps in vocabulary between students from families with low and higher incomes.

State law now allows for grade retention if children are not reading proficiently by third grade, so the stakes are high—particularly for students of color who are disproportionately at risk of retention. For the retention legislation to be successful and avoid contributing to racial and ethnic inequities, it is critical that there be sufficient funding for the services needed to address the cumulative impact of inadequate early learning opportunities for children of color, including the early identification and treatment of developmental delays and high-quality child care and preschool.

While some improvements have been made in improving access to child care, there is much more work to be done to ensure that children are healthy and ready to learn, to expand the state’s Early On program and other efforts to identify developmental problems early, to improve child care quality as well as access to early learning, and to adequately address reading problems prior to third grade. For 2018, the Legislature approved:

- Increased funding for early literacy coaches. For 2018, $3 million in new funds will be available to double the amount available for early literacy coaches to $6 million statewide.

- The consolidation of other early literacy funds. The Legislature consolidated a total of $20.9 million that is currently allocated to early literacy for professional development, screening and diagnostic tools and added instructional time—with funds to be distributed to districts in an amount equal to $210 for every first grade student. Funding for professional development and diagnostic tools are both capped at 5%.

Failed to invest in adult education. Despite a high level of need, state funding for adult education has dropped by 70% since the 2001 budget year. For 2018, the Legislature provided continuation funding of $25 million for adult education programs, along with $2 million for pilot programs focused on career and technical education.

More than half of adult education students read below the eighth-grade level, and over one quarter (27%) list English as their second language.35 Adult education is an important tool for improving educational achievement and adult literacy, which are critical to a two-generational approach for lifting children out of poverty and improving the state’s economy. Sadly, only 5% of Michigan adults who do not speak English “very well” enroll in English as a Second Language adult education programs, and only 7% of the over 210,000 Michigan adults ages 25-44 who lack a high school diploma or GED are enrolled in adult education.36

Continued Michigan’s sad tradition of providing too little financial aid for students with low incomes. College tuition more than doubled at almost every state university between 2003 and 2015, making the state’s average tuition cost the sixth highest in the nation and second highest in the Midwest during the 2015-16 school year.

As a result, 2 of every 3 Michigan college students graduate with debt, which averaged nearly $30,000 in 2014. While there is no state data by race and ethnicity, national studies have found that African-American students and their families owe significantly more in student debt (averaging over $43,000), and Latino parents and grandparents incur the most student debt on behalf of their children.37

Further, Michigan invests far less in needs-based scholarship grants proportional to its student population than most other states, and has completely eliminated state financial aid for students who have been out of high school for more than 10 years. Michigan currently spends less than half the national average of state spending on needs-based tuition grants. Given the barriers that young people of color face in being prepared for and able to afford college, the lack of investment in financial aid is a clear component of the cumulative impact of racial and ethnic disparities in educational achievement and ultimately earnings.

There is a direct correlation between state support for public universities and tuition costs, and between 2003 and 2017, Michigan cut university funding by more than $262 million, a 30% decrease in public support after adjusting for inflation. For 2018, Michigan lawmakers:

- Tightened the tuition cap for universities. Michigan has adopted a “tuition restraint” policy requiring public universities to limit tuition increases to no more than 3-4% each year in order to receive full state funding. While a small move in the right direction, given the steep tuition increases that universities have already put in place, this change does little to reduce the high cost burden faced by students in Michigan universities, and precludes many young people of color from entering and completing four-year degree programs.

- Slightly increased funding for financial aid programs. The amount of the grants is still not enough to significantly help students pay high tuition costs, however.

- Failed to provide financial assistance for students who have been out of high school more than 10 years. The Part-Time Independent Student Grant, which helps older students, was eliminated in 2010. There have been efforts since 2015 by the Legislature and the governor to reinstate the grant, but they have failed to be signed into law. For the 2018 budget year, the governor recommended $2 million for the grant, but the Legislature rejected that proposal.

ENDNOTES

[types field=’download-link’ target=’_blank’][/types]

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders.

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders. Jacob Kaplan

Jacob Kaplan

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.  Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget.

Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget. Donald Stuckey

Donald Stuckey  Patrick Schaefer

Patrick Schaefer Alexandra Stamm

Alexandra Stamm  Amari Fuller

Amari Fuller

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.