Introduction

Michigan’s economy depends on having skilled workers. In the past, high school graduates could enter the middle class by getting jobs in the manufacturing sector immediately after graduation and moving eventually into skilled, higher‐paying positions. Today, however, technological advances and offshore production have greatly decreased the need for low-skilled, entry‐level labor, and their prospects will likely be made worse by the economic fallout from COVID-19, one result being that many businesses have been forced to scale down or close altogether. A high school diploma by itself has far less value in the job market than in past decades, and employers increasingly prefer to hire skilled workers with a postsecondary credential such as a degree, certificate or license. Consequently, workers with some level of postsecondary education have better wage and employment outcomes.

Governor Whitmer has declared the “Sixty by 30” campaign to establish a state goal of 60% of Michigan residents completing a postsecondary certificate or degree by the year 2030. Her plan to achieve that includes implementing a financial aid program for older students, strengthening financial aid for traditional students, and providing incentives for schools to increase their student completion rate of the Free Application for Financial Student Aid (FAFSA).1 It should be noted that this is a relatively modest state goal; of the 44 states with a postsecondary attainment goal, half have set it at 60%, while only three have set it at a lower level (55%) and 19 states have set it higher (most ranging from 65% to 70% and Oregon at 80%).2

Governor Whitmer has declared the “Sixty by 30” campaign to establish a state goal of 60% of Michigan residents completing a postsecondary certificate or degree by the year 2030. Her plan to achieve that includes implementing a financial aid program for older students, strengthening financial aid for traditional students, and providing incentives for schools to increase their student completion rate of the Free Application for Financial Student Aid (FAFSA).1 It should be noted that this is a relatively modest state goal; of the 44 states with a postsecondary attainment goal, half have set it at 60%, while only three have set it at a lower level (55%) and 19 states have set it higher (most ranging from 65% to 70% and Oregon at 80%).2

Unfortunately, however, Michigan college students face increasingly high tuition costs. Many nontraditional students, those who are age 25 and older and who are often raising children and/or in the workforce, cannot get state financial aid. Financial aid even for “traditional students” (those who enter college immediately after high school graduation) hasn’t kept up with tuition costs, leading many students—particularly students from households with low incomes and students of color—to take on an unprecedented level of student loan debt that will follow them far beyond credential attainment. Such debt can be expected to depress spending by recent college graduates and young professionals, causing local businesses and the state coffers to lose out on revenue even during strong economic periods. Some individuals may avoid college altogether to avoid the expenses and debt, robbing the state labor pool of potential skilled workers.

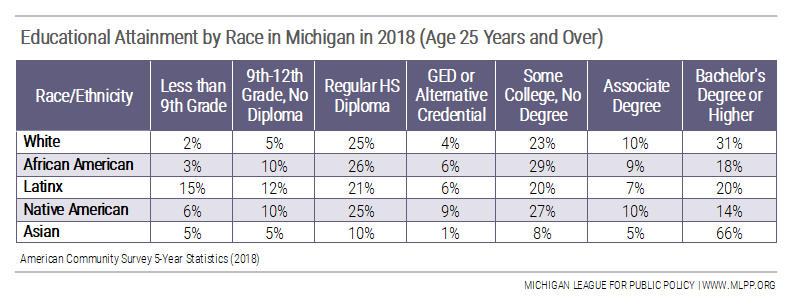

Michigan Has Stark Racial Disparities in Educational Attainment

Of particular concern are the racial disparities in access and completion of postsecondary education. In Michigan, only 14% of Native American, 18% of African American and 20% of Latinx adults age 25 or over possess a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 31% of White adults and 66% of Asian adults.3 Native American, Latinx and African American adults also tend to lead the other two racial groups in the percentage without a high school diploma.4

For African American Michigan residents, educational attainment varies among population centers, ranging from higher than 35% in some southeast Michigan suburbs such as Farmington Hills and Southfield to below 10% in some medium-sized cities such as Saginaw, Muskegon and Benton Harbor.5

There are several possible explanations for the educational disparity among Black population centers. One explanation may be that higher education seems out of reach to many who live in high-poverty cities that are distant from major population centers, such as Benton Harbor. Another may be that some medium-sized cities were historically dependent on manufacturing jobs and college was not seen in decades past as important for achieving middle-class economic security. Another explanation could be that college-educated African Americans, like college-educated individuals in general, tend to move to areas of the state with more opportunities and better-paying jobs, such as Southeast Michigan or the Lansing or Grand Rapids areas, rather than move to or return to high-poverty cities like Benton Harbor and Muskegon. In the latter scenario, cities with more poverty may experience a vicious cycle in which even if they increase the number and percentage of high school graduates who go on to college, those graduates are less inclined to return and spend their money locally to generate economic activity. Importantly, there are educational disparities resulting from the impact of economic inequality on children and their school readiness, school funding systems that do not recognize the added costs of teaching children in high-poverty schools, and lower high school completion rates.

Racial Disparities Exist in Access to and Completion of a Four-Year Degree

Racial Disparities Exist in Access to and Completion of a Four-Year Degree

Likely contributing to the racial disparities in Michigan’s educational attainment are the disparities in enrollment and completion within Michigan’s public universities. In a study of Black student representation in public universities in 43 states, the Education Trust found that Michigan falls far short in African American racial equity in bachelor’s degree attainment and university representation relative to state demographics:

- Michigan is one of eight states that would have to more than double the number of African American students earning bachelor’s degrees to match state demographics.6

- In its share of Black undergraduates enrolled at public four-year institutions relative to its share of Black residents, Michigan is third-worst (39th out of 41 states measured) in the nation. While the Black share of the state population that is age 18-49 with a high school diploma but no bachelor’s degree is 17.1%, the share of public university undergraduates who are Black is only 8.7%.7

- Michigan is similarly third-worst in its share of bachelor’s degrees earned by Black students relative to its share of Black residents. The share of bachelor’s degree holders (with degrees earned at four-year universities) who are Black is only 6.8%, but it should be closer to 17.1% in order to match the Black share of the state population age 18-49 with no bachelor’s degree.8

- While around half of the states studied have double-digit gaps between the shares of Black and White graduates who are awarded a bachelor’s degree, Michigan is one of six states with gaps greater than 15 percentage points (15.8). The average state gap is only 7.7 percentage points.9

Of Michigan students who enrolled in a four-year public university for the first time in the 2012-2013 school year, 80% of Asian and 78% of White students received a credential (usually a bachelor’s degree) within six years, while only 69% of Latinx, 59% of Native American and 55% of African American students did so.10 The disparity is especially pronounced with African American students, as barely above one quarter graduated within four years—far below most other racial groups.11

There is also some segregation in the distribution of Michigan’s students of color among Michigan’s fifteen public universities, with African American students comprising 30% of Eastern Michigan University’s 2017 freshman cohort, but only 4% of that of its geographical neighbor, University of Michigan—Ann Arbor.12 In the Upper Peninsula, students at Michigan Technological University and Northern Michigan University are 89% and 85% White, respectively. Native American students comprise only 1% of students at both universities, but comprise 6% of the students at the other university in the Upper Peninsula, Lake Superior State.13 (For a detailed table, see Appendix A.)

The disparities in four-year degree attainment have implications for Michigan’s economic future. Skilled workers help attract and keep businesses in the state, spend more in their local communities, pay more in taxes, and are less likely to become unemployed or need public assistance. On the other hand, not addressing racial and income disparities in postsecondary access and completion keeps a segment of the population out of the skilled labor pool, increases family economic vulnerability, slows the revitalization of struggling communities, wastes an opportunity to increase state revenues, and makes the state a less desirable place for highly educated persons of color to move to.

Disinvestment in State Funding for Universities Has Resulted in Large Tuition Increases

Michigan has drastically cut funding to its public universities in the past twenty years. The largest cuts came during the period between 2000 and 2010, during which time total funding for university operations was slashed by nearly $38.5 million, not accounting for inflation. Between 2010 and 2020, $10.6 million of the cut had been restored, but after adjusting for inflation, universities received $667 million less in 2020 than they had in 2000 and $243 million less than they had in 2010. If each university had had its allotment for Budget Year 2000 increased just for inflation each year, the total appropriation for university operations in 2020 would have been $2.14 billion rather than $1.47 billion.14

The state disinvestment in public universities has led to sharp increases in tuition to make up the difference. Whereas in 2000, universities received approximately $6,949 per full-time equivalent (FTE) student in tuition and $10,040 per FTE student in state appropriations, by 2018 they received $14,288 per FTE student in tuition and only $6,150 per FTE student in state appropriations, with the student share of the cost of university operations going from 41% to 70%. This puts Michigan’s student share of college expenses at sixth-highest in the country, and highest in the Midwest. Illinois students, by comparison, pay only 35% of college operational expenses, as the state pays twice per FTE student what Michigan does.15

As a result of state disinvestment, tuition at nearly all universities has tripled in nominal dollars since 2000, and more than doubled after adjusting for inflation. Most of the increase took place between 2000 and 2010, while Michigan was in a recession and also struggling with structural budget shortages due to tax cuts. Michigan State University, for example, went from a sticker-price tuition level of $5,004 for the 1999-2000 academic year to $15,645 for 2019-2020.16 If MSU had increased its tuition only for inflation during that time, its 2019-2020 tuition would have been only $7,138. Although many states around the country have increased their college costs for students, Michigan’s tuition has been ranked by The College Board to be the sixth-highest average tuition in the nation.17

Tuition Restraint Is too Little, too Late to Contain Costs to Students

In Budget Year 2012, after a decade of state funding cuts to Michigan universities and the resulting tuition increases, Michigan put into place a tuition restraint requirement in which universities must either keep tuition increases below a specified maximum percentage or forfeit their allocation increases. While this is a sound strategy for discouraging further large increases, it does not address the $667 million funding cut to universities between 2000 and 2020, nor does it make up for the more than doubling of tuition (after adjusting for inflation) during that time. The damage to students due to higher out-of-pocket costs has already been done, and all tuition restraint accomplishes is to limit the extent of further damage.

A superior but more costly alternative to tuition restraint would be tuition reduction, which would require significant investment by the state. The ideal tuition reduction solution, though politically and fiscally unattainable in the current environment, would be to use Budget Year 2000 funding as a baseline and restore the $667 million by which current year funding falls short of that year, appropriating $2.1 billion for university operations while requiring universities to charge tuition at 2000 levels adjusted for inflation. Short of that, the state could explore what level of funding would be adequate for incentivizing each university to decrease tuition by a significant percentage, and commit to that level of funding with an increase for inflation each year in exchange for the university only raising its tuition for inflation.

North Carolina offers two models to keep tuition affordable that may be instructive. One is the Fixed Tuition Program, which fixes tuition rates for all resident bachelor’s degree-seeking incoming students at all UNC institutions for eight consecutive semesters.18 This provides predictability for students and their families as they financially plan for their college expenses. Another is the North Carolina Promise, in which three universities in Fall 2018 began charging in-state undergraduates just $500 tuition per semester, and out-of-state students just $2,500 per semester.19 One drawback with Michigan adopting something similar to the North Carolina Promise is that, because it is only used at a limited number of universities, it has the potential to create a situation in which Michigan universities become segregated by income.

At least one Michigan university has a tuition scale in which students can attend free based on household income. University of Michigan—Ann Arbor has the Go Blue Guarantee, which provides free tuition for students from families with incomes at or below $65,000 and assets below $50,000, and tuition support for students from families with income between $65,000 and $180,000. While this may sound like an ideal program for other Michigan universities to adopt, the Go Blue Guarantee is funded in large part by private donations and thus would be difficult to replicate across universities via state policy.20

Financial Aid

Michigan currently has three need-based financial aid programs: the Tuition Incentive Program, which serves students from Medicaid-eligible households; the Michigan Tuition Grant, which is available only to students attending a private, not-for-profit institution; and the Michigan Competitive Scholarship, for which eligibility is based on both need and merit. Michigan also offers the Indian Tuition Waiver, which waives all community college and public university undergraduate tuition costs for members of federally-recognized Native American tribes, and reimburses universities and community colleges for the foregone tuition.

While Michigan has three need-based financial aid programs, the Tuition Incentive Program is the only program in which need is based on household income rather than estimated family contribution and specifically targets students from families with low incomes. To be eligible, a student must have been in a family that had a qualifying form of Medicaid for 24 months—in other words, had been below 130% of the poverty line—within a 36-consecutive month period between age nine and high school completion. Students as young as 12 who are identified as meeting the Medicaid eligibility requirement are sent notifications encouraging them to complete the TIP application, and must also file a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) form. TIP provides two years of tuition-free community college in Phase I, and up to $500 per semester ($2,000 total) for third- and fourth-year classes at a public university or a private not-for-profit four-year college. Students receiving TIP are also often eligible for other financial aid such as the federal Pell Grant, the Michigan Competitive Scholarship, and, if attending a private not-for-profit, the Michigan Tuition Grant.

Unfortunately, Michigan is the stingiest state in the nation for financial aid, devoting the fewest financial aid dollars per full-time equivalent community college or public university student ($4 in 2018, compared to $1,233 by Indiana), and devoting the smallest share of educational appropriations to financial aid for students at public institutions (.1%, compared to 19.2% by Indiana). While five of the six Upper Midwest states are below the national average in both of these categories, Michigan is significantly lower than its peers.21

Recognizing that addressing college costs is a key component of increasing the number of Michigan residents with postsecondary credentials, Governor Whitmer has introduced two additional financial aid programs to address the expenses of postsecondary education and to better prepare the future labor force. Michigan Reconnect would provide debt-free tuition (as a last-dollar aid program) for up to two years for students over age 25 who have a high school diploma but not a two- or four-year degree, and the Michigan Opportunity Scholarship would provide high school graduates with two years of either tuition-free community college or tuition-reduced study at a four-year college or university. Legislature enabling Michigan Reconnect has been passed with bipartisan support and was scheduled to begin in the 2020-2021 school year, but funding for it was pulled from the budget due to the need for emergency funding to respond to the coronavirus.

During the COVID-19 emergency period in Michigan, Gov. Whitmer also proposed what she called a GI Bill for the workers who served on the frontlines of the coronavirus by providing essential services to the public, such as grocery store workers, health workers, child care providers and sanitation collectors. The program, called Future for Frontliners, would provide “a tuition-free pathway to college or a technical certificate to essential workers who don’t have a college degree.”22 Details of the proposal were not available at the time of this writing.

The proposed Michigan Opportunity Scholarship would expand the concept of Phase I of the Tuition Incentive Program to a broader population and reach low-income students further up the income scale. Path I, like Phase I of the TIP, provides graduating high school students with two years of tuition-free postsecondary education at a community college toward a certificate, an associate degree, or a transfer to a four-year institution. However, while the TIP is available only to students from Medicaid-eligible families who enroll within four years of completing their high school diploma, Path I of the Opportunity Scholarship would be available to all students regardless of income level who enroll the fall immediately following graduation. If the student wishes to attend a four-year public or a private not-for-profit college or university rather than community college, Path II of the Opportunity Scholarship provides $2,500 in tuition assistance annually for the first two years. Path II, unlike Path I, is income-targeted, and is available only to students from families with an annual household income below $80,000.

Taken together, the Tuition Incentive Program and the Michigan Opportunity Scholarship are a significant step in ensuring that students from families with low incomes who want to get a bachelor’s degree have a path to do so—for the first two years of the four-year degree. However, it is also important that such students be able to complete the final two years of bachelor’s degree work without incurring a large amount of debt, and the Opportunity Scholarship provides no help for the third and fourth year. Medicaid-eligible students attending public universities during the third and fourth year can receive $1,000 per year from Phase II of the TIP, along with a maximum of $1,000 from the Competitive Scholarship and additional aid from the Pell Grant. However, this falls far short of the average public university tuition of $13,777 per year, and to pay the difference, students would need to work a significant number of hours, take out student loans or receive last-dollar private or institutional scholarships.

It is encouraging to note that there has been a significant increase in the use of the TIP for the third and fourth year at each of Michigan’s 15 public universities, from a total of 1,645 in the 2012-13 school year to 6,226 in the 2017-18 school year. However, each year there are between 930,000 and 1.02 million children in families who receive Medicaid. Given that TIP eligibility is based on a student’s family having had a qualifying form of Medicaid for 24 months within a 36-consecutive month period when the student was between age nine and high school completion, a yearly total of 6,226 third- and fourth-year students using TIP at public universities appears to be a very small percentage of the total college-age individuals who would be eligible.

Many students and their families may mistakenly believe that they will not qualify for enough financial aid for college to be affordable. Because completion of the FAFSA is required for all public student aid programs, the governor has initiated the “FAFSA Challenge” that provides recognition and monetary prizes to high schools that significantly increase their FAFSA completion rate, with the goal of increasing the statewide FAFSA completion rate from 56% in 2019 to 75% in 2020. However, students from families with low incomes or who are unfamiliar with the college application process may find filling out the FAFSA and providing income verification onerous, and many would likely benefit from assistance from a high school counselor.

To achieve a 75% FAFSA completion rate, Michigan should commit to and invest in increasing its number of high school counselors. Michigan ranks near the bottom in the nation for counselor-student ratios with 729 students per counselor, and it is estimated that the state would need to hire 1,100 more counselors at a cost of $80-100 million more per year just to reach the still-high national average of 482 students per counselor.23 High schools in low-income communities with low college attainment need more than pep talks and incentives for raising their FAFSA completion rates; they need state support and investment to back it up.

Three states—Illinois, Louisiana and Texas—go further than Michigan’s FAFSA Challenge by requiring FAFSA completion as a requirement for high school graduation. Louisiana was the first state to do so, with the policy in place beginning in the 2017-18 school year. Louisiana brought its completion rate for public school students up from approximately 50% in 2015 to 85% in 2019, including an 83% rate for economically disadvantaged students, an 82% rate for homeless students and an 86% rate for African American students. (The Latinx rate was relatively lower at 69%, but that is still higher than Michigan’s overall FAFSA completion rate.)24 This is something that Michigan may want to consider in the future, but because it is important that such a requirement not become yet another hurdle to graduation for struggling high school seniors, a FAFSA mandate for graduation must be backed up with money for additional counselors and other student supports.

College Debt Affects Many Students, but Disproportionately Affects Students of Color

In the class of 2018, 59% of college graduates took out student loans and owed an average of $32,158 on those loans, putting Michigan in the top ten of high-debt states. While a high level of student debt can depress spending among those with bachelor’s degrees and professional salaries, these figures do not include students who took out loans but did not graduate. Such students are at a greater disadvantage than their degree-holding counterparts, as the salaries for those with “some college, no degree” are considerably less on average than those with a bachelor’s degree.

There are glaring racial disparities in the United States and in Michigan in the amount of debt students graduate with. Nationally, Black graduates, upon earning their bachelor’s degree, owe on average $23,400 while their White peers owe $16,000.25 Over the next few years, the black-white debt gap more than triples from $7,400 to $25,000.26 Black graduates are also more likely to take out student loans (81%) than White students (63%).27

In Michigan, while it is difficult to pinpoint by race the extent of debt, there are glaring disparities in the rate of default of those who live in communities of color compared to those who live in majority-White communities. Statewide, 15% of student loan holders are in default, but when the default rates are broken down by ZIP code, communities of color have a default rate that is twice as high at 30%.28 Michigan leads the Midwest in both the percentage point gap (18 percentage points) between majority-White communities and communities of color, but also in the communities of color default rate, which is sixth highest in the nation. Saginaw and Genesee counties have particularly high default rate disparities, with 29 and 28 percentage points, respectively.29

A recent study shows that, when taking out private loans or refinancing student loans, there may be racial disparity in the interest paid by students with low incomes or students of color based on the institutions they attend. The study found that some lenders charge more interest to borrowers taking out a private loan to attend a community college than to those attending a four-year college, and that borrowers who refinance their student loans with some lenders pay more if they attended a historically Black college or university or a Hispanic-serving institution.30

Granting Equal University Access to Undocumented Students is Good for Our State

One way to help more students of color in Michigan access a university education and attain a bachelor’s degree is to allow Michigan’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) residents and other undocumented immigrants to attend Michigan’s public universities at in-state tuition levels and have the same access to financial aid. However, Michigan’s two need-based financial aid programs for public universities both exclude students who are not “a U.S. citizen, permanent resident, or approved refugee.”31 While excluding DACA immigrants from financial aid is done ostensibly to save the state money, that rationale ignores the fact that enabling Michigan’s DACA immigrants to increase their value in the job market will benefit Michigan’s economy. Higher-earning residents pay more in taxes, spend more money in their local economies and are often better able to contribute to the social life of their communities through philanthropy and civic engagement.

Because Michigan’s universities are structurally independent and can set their own policies for admission and institutional aid, there is variance among the fifteen universities in their policies and practices regarding DACA and other undocumented immigrants. The National Forum on Higher Education for the Public Good, housed at the University of Michigan—Ann Arbor, has evaluated universities around the country on accessibility for undocumented immigrants with regard to admissions, tuition, financial aid and general support.32 Among Michigan universities, Grand Valley State University, Oakland University and University of Michigan—Ann Arbor were rated most accessible, while Eastern Michigan University was rated least accessible.33 Inaccessibility is rated not only on the basis of policy itself, but also whether the information is clear on the university’s website (i.e. are DACA students specifically mentioned, or does the website give the impression that they are treated the same as international students for tuition purposes?).

Prison Postsecondary Education

There is an unfilled skills need in Michigan that can be met, at least in part, by enabling incarcerated individuals to take college classes and leave prison with a degree or other credential. Earning a degree while in prison can also greatly reduce an individual’s chance of recidivism by 43%, and every dollar invested in prison education saves four to five dollars in cost savings related to recidivism.34 Prison education also improves behavior and morale within the prisons and benefits incarcerated individuals’ self-identity, mental health, and social and familial relationships.35 Yet there are two major barriers to such individuals having access to college: a lack of education and training opportunities in many Michigan prisons and prohibitions against incarcerated students receiving most public financial aid.

Incarcerated students have been barred from receiving Pell Grants since 1994 when then-President Clinton signed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. The Vera Institute for Justice estimates that if the Pell Grant ban were lifted, about 463,000 incarcerated people nationally would be eligible for Pell Grants.36 A program developed in 2016, the federal Second Chance Pell Experimental Sites Initiative, provides the equivalent of a Pell Grant to about 12,000 individuals nationally each year, including 583 Michigan prison residents taking classes from 110 course offerings in the fall of 2017.37

Of Michigan’s financial aid grants, only the Tuition Incentive Program is currently available to individuals in prison, having been made available to that population in the 2020 budget. However, the TIP is restricted to only those who have been out of high school for less than ten years, and many prison residents do not fit that eligibility criteria. Most individuals who could benefit from college programs must rely on private donations to participate.

While all prisoners have the right to take college classes by mail in Michigan, many Michigan prisons do not have any face-to-face college instruction within their walls. This leaves behind many incarcerated individuals who would do well in such programs and contribute to the economy after their release. Michigan should develop a plan to make college instruction available to a larger number of prison residents who wish to participate.

Recommendations

University Funding and Tuition Costs

Replace or augment the current tuition restraint system with a tuition reduction system. Universities that reduce their tuition costs by a given percentage would be awarded a comparable increase in state funding, with long-term assurance of that funding if they keep their tuition at the reduced rate adjusted for inflation.

Financial Aid

Enact the proposed Michigan Opportunity Scholarship that provides two years of tuition-free community college. For students who aspire to attain a four-year degree, this helps to ensure that finances will not be a barrier during the first two years.

Strengthen financial aid for students in their third and fourth year of receiving a bachelor’s degree at a public university. While the first two years of college are covered by the Tuition Incentive Program and/or the proposed Michigan Opportunity Scholarship, depending on a student’s income level, the final two years are not covered by as much financial aid and can prompt students to take out expensive loans or work more hours than they can handle while in school.

Increase the number of high school guidance counselors in schools that serve large numbers of students with low incomes and students of color. A 729:1 student-counselor ratio does not enable students, especially those from households with low incomes or who aspire to be first-generation college students, to receive the kind of guidance they need in seeking out college options and financial aid. Michigan should invest the money needed to ensure that all high schools have an adequate number of counselors.

Increase outreach by public agencies and nonprofit service providers that serve families with low incomes to make them aware of the Tuition Incentive Program. One reason for the underutilization of the TIP by college-age individuals from Medicaid-eligible families may be a lack of information about financial aid that is available. Michigan should invest in increasing the outreach to families receiving public assistance to let them know about TIP and other financial aid that is available.

Explore ways to strengthen FAFSA promotion, including requiring FAFSA completion as a prerequisite for high school graduation with ability for some populations to opt out. While the FAFSA Challenge is a good start, it should be evaluated after a couple years to determine whether it is sufficient in encouraging enough students to go to college to meet Michigan’s postsecondary credential goal.

University Access for Undocumented Residents

Grant in-state tuition eligibility to in-state DACA residents at all Michigan public universities. As part of the drive to achieve 60% of residents having a postsecondary credential by 2030, the governor’s budget should include boilerplate in university funding appropriations bills that clarifies that in-state DACA residents pay the same level of tuition as other in-state residents.

Remove the citizenship or permanent residency requirement from the Tuition Incentive Program and the Michigan Competitive Scholarship. For the Tuition Incentive Program, the language that states that a student “be a United States citizen and a resident of this state according to institutional criteria” would need to be removed from boilerplate language in the higher education appropriations bills. The bills do not contain similar language for other need-based financial aid programs, so changes to eligibility for those programs can be done departmentally.

University Education in the Prisons

Make more state aid available to those in Michigan’s prisons who otherwise qualify. Michigan recently made the Tuition Incentive Program available to incarcerated individuals. The state should go further and make other financial aid available as well, including Michigan Reconnect program for students 25 years and older, the other longtime state need-based financial aid programs (the Michigan Competitive Scholarship and the Michigan Tuition Grant), and the proposed Michigan Opportunity Scholarship.

Increase the number of university and community college prison programs. Michigan’s Department of Corrections should work with state universities to increase the number of prisons offering face-to-face university instruction, with the goal of making college opportunities available to all prisoners with interest who qualify, regardless of where they are housed.

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders.

Emily Jorgensen joined the Michigan League for Public Policy in July 2019. She deeply cares about the well-being of individuals and families and has a great love for Michigan. She is grateful that her position at the League enables her to combine these passions and work to help promote policies that will lead to better opportunities and security for all Michiganders. Jacob Kaplan

Jacob Kaplan

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.

Mikell Frey is a communications professional with a passion for using the art of storytelling to positively impact lives. She strongly believes that positive social change can be inspired by the sharing of data-driven information coupled with the unique perspectives of people from all walks of life across Michigan, especially those who have faced extraordinary barriers.  Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget.

Rachel Richards rejoined the League in December 2020 as the Fiscal Policy Director working on state budget and tax policies. Prior to returning to the League, she served as the Director of Legislative Affairs for the Michigan Department of Treasury, the tax policy analyst and Legislative Director for the Michigan League for Public Policy, and a policy analyst and the Appropriations Coordinator for the Democratic Caucus of the Michigan House of Representatives. She brings with her over a decade of experience in policies focused on economic opportunity, including workforce issues, tax, and state budget. Donald Stuckey

Donald Stuckey  Patrick Schaefer

Patrick Schaefer Alexandra Stamm

Alexandra Stamm  Amari Fuller

Amari Fuller

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Renell Weathers, Michigan League for Public Policy (MLPP) Community Engagement Consultant. As community engagement consultant, Renell works with organizations throughout the state in connecting the impact of budget and tax policies to their communities. She is motivated by the belief that all children and adults deserve the opportunity to achieve their dreams regardless of race, ethnicity, religion or economic class.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Megan Farnsworth joined the League’s staff in December 2022 as Executive Assistant. Megan is driven by work that is personally fulfilling, and feels honored to help support the work of an organization that pushes for more robust programming and opportunities for the residents of our state. She’s excited and motivated to gain overarching knowledge of the policies and agendas that the League supports.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Yona Isaacs (she/hers) is an Early Childhood Data Analyst for the Kids Count project. After earning her Bachelor of Science in Biopsychology, Cognition, and Neuroscience at the University of Michigan, she began her career as a research coordinator in pediatric psychiatry using data to understand the impacts of brain activity and genetics on children’s behavior and mental health symptoms. This work prompted an interest in exploring social determinants of health and the role of policy in promoting equitable opportunities for all children, families, and communities. She returned to the University of Michigan to complete her Masters in Social Work focused on Social Policy and Evaluation, during which she interned with the ACLU of Michigan’s policy and legislative team and assisted local nonprofit organizations in creating data and evaluation metrics. She currently serves as a coordinator for the Michigan Center for Youth Justice on a project aiming to increase placement options and enhance cultural competency within the juvenile justice system for LGBTQIA+ youth. Yona is eager to put her data skills to work at the League in support of data-driven policies that advocate for equitable access to healthcare, education, economic security, and opportunity for 0-5 year old children. In her free time, she enjoys tackling DIY house projects and trying new outdoor activities with her dog.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Amber Bellazaire joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a policy analyst in June of 2019. Her work primarily focuses on state policy and budgets affecting Michigan’s Medicaid programs. Previously, Amber worked at the National Conference of State Legislatures tracking legislation and research related to injury and violence prevention, adolescent health, and maternal and child health. She also brings with her two years of Americorps service. As a full time volunteer, Amber had the opportunity to tutor high school students in Chelsea, Massachusetts and address issues of healthcare access and food insecurity through in-person outreach in Seattle, Washington.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.

Simon Marshall-Shah joined the Michigan League for Public Policy as a State Policy Fellow in August 2019. His work focuses on state policy as it relates to the budget, immigration, health care and other League policy priorities. Before joining the League, he worked in Washington, D.C. at the Association for Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), providing federal policy and advocacy support to nonprofit, Medicaid health plans (Safety Net Health Plans) related to the ACA Marketplaces as well as Quality & Operations.